Writing About Real People

Wednesday is about books, and reading, and writing. Today, I’m thinking about how I go when writing about real people.

Journalists write about real people. So do poets, and storytellers, and bloggers too. I have been writing about real people in a variety of formats, and under a couple of different names, for the best part of 30 years now. I started interviewing people, nervously, struggling of course, when I was in my early/mid 20s. The first couple of times I did phoners, I felt bad that they didn’t go anywhere; didn’t have the platform. After a while, I had interviews coming out my ears (as it were) and for a brief time there I was writing a bunch of music reviews and interviews for Wellington’s Dominion Post newspaper, and I was writing music and film reviews, and interviews, under the pen-name Mark Reid:

Mark Reid: Film Reviewer

It was never my idea to run under a pseudonym and I did it with a clunkiness that was weirdly endearing, I hope — but probably, actually, just baffling. I’d interview Anika Moa, or Savage, or Anna Coddington as, ostensibly, myself. And then without saying anything it would appear in print at the end of the week in the Herald on Sunday as written by Mark Reid. It didn’t matter to me, I was being paid. And I hid under the generic fake name because I wanted to maximise my freelancing. I was reviewing in a bunch of places, and working a full time job too. I wasn’t really on social media back then, didn’t have a kid, my “blogging” days were only just getting going. I guess I found the time, pretty easily. There were international acts that I interviewed too — David Coverdale was hilarious, Ozzy Osborne never quite happened in the end, alas! — but they knew to ask for ‘Simon Sweetman’, or knew that was who was calling. Obviously they weren’t being sent copies of what ‘Mark Reid’ wrote.

The pen-name was short-lived, the Herald’s new editor panicked, and said I had to write under my own name or not at all, and I made the call to stay writing for the paper in the city where I lived, because that was the smart call at the time, even though the Auckland money was better. If I’d known how brutally I’d be thrown under the bus by cowards when Mr Betterman, Robbie Williams threw his toys, I’d have been smarter to ditch the Wellington paper and stay on in Auckland maybe…

But then again, not really eh…

Anyway, in either way, there’s a contract; an understanding. You’re the journalist (or “blogger”, since that always seemed to matter for people to say as some thin insult). And you’re there to do the job, the (real) person wants to be in print, even if it wasn’t always under the pen of someone using their real name.

But what about stories, poems, essays, blogs, and Substack newsletters? What’s the deal then eh?

My dad didn’t really like being a feature of my poems — many of them posted to Facebook before a bunch of them were collected in a book. I always meant them with love, they were endearing — even if sometimes I seemed baffled (the version of me in the poem) or I described lines he said or behaviour he threw out as baffling; it was always meant with love.

He wasn’t the only one of course. My mum, my brother, various family members have made it into print. There was a brutal poem about my brother that I removed from my first book of poems. It was all about how I took my very first book (of music journalism) up to Auckland to show to my family. I didn’t want to, because I knew they wouldn’t really care. They are more interested in jobs that pay lots of money, and houses you can rent out, and I felt like a published book (the first copy) was just going to sit there. Anyway, against my better judgment I packed it for the trip. And it sat there all weekend, for the huge amount of words I’d collected, suddenly the book said absolutely nothing.

Many years later I wrote about it, and I still really like the poem, but geez I got an attack of the guilts when I read it back in the final editing stage, and I asked for it to be removed. I replaced it with an actually endearing poem about my brother, which was all about us laughing at the rhino pissing while visiting the Auckland zoo. We were adults, with our own kids in tow. But the one and only other time we’d been there together was when we were kids ourselves. So the memories were flooding back, as we were trapped in hysterical laughter. That was a better poem for the book. Still a real story about a real person, but kinder, I suppose. A nicer thing to have in print.

But I don’t feel bad about writing the other poem. I just felt bad at the idea that he and others might see it — true to the form of my first published book, he’s never actually read that book of poems, so I should have just published, and not even risked being damned.

It’s a fascinating thing though, writing about real people.

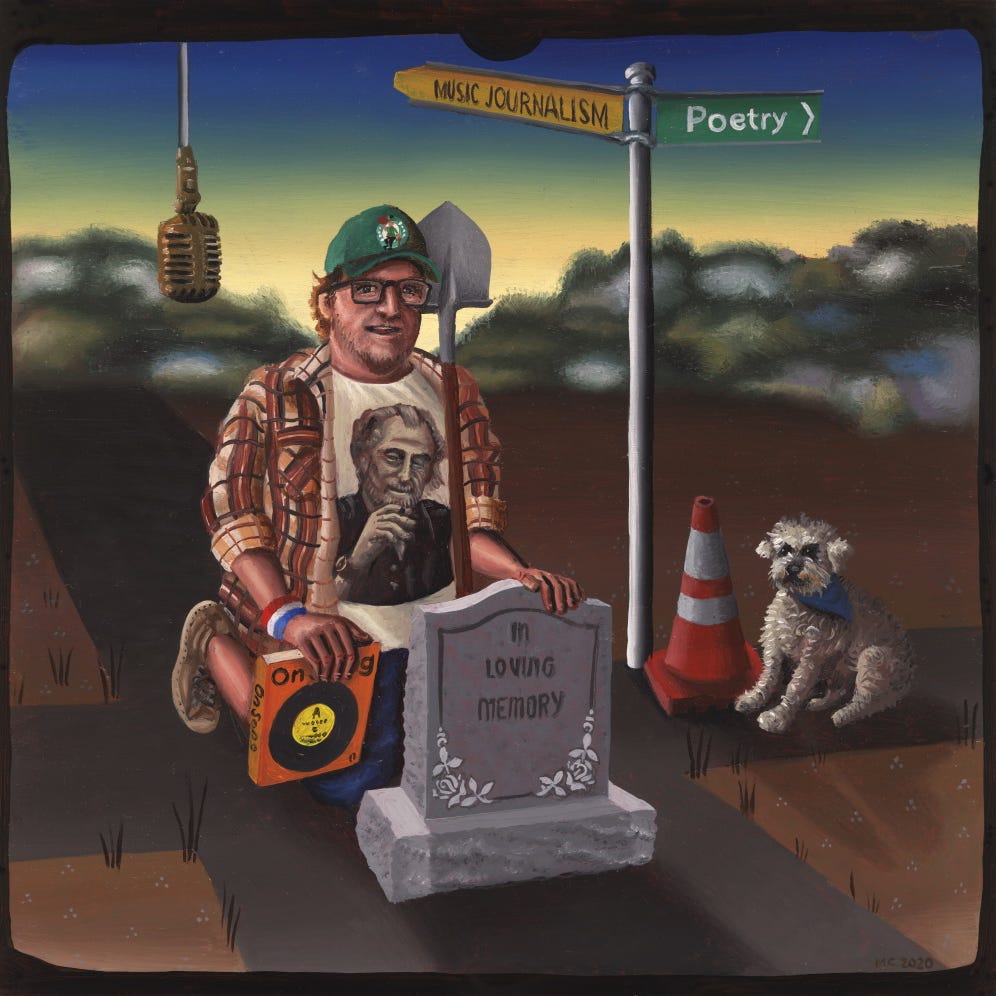

My second book of poetry, released just last month, The Richard Poems, is based on true stories. It is about a real person. I didn’t hide that. I did not ask permission. I did not feel I needed to. It is my story after all, my version, and I am open and up for the fact that he, or someone else could write The Simon Poems, or something similar. And many people used to in comments under my blogs on Stuff, on Facebook, in letters to the Editor, and briefly, most ghastly of all, on a Reddit thread. They never asked for permission to do that, and they never had to. The contract is still there, even if more awkward and somewhat elastic in the way it’s implied.

It’s murkier with fiction — because of course I have taken things and stated them in a way. I have played with the stories to shape themes, I have been faithful to my memory, and my version of how it all played out, but I have tried to fashion it into fiction; it has to survive as a story (or stories) that do not require knowledge of the real person; the real person is there because a) it really happened, he really existed, we both really existed — and b) because through that specificity I can reach for something more universal as a result. At least, I hope so eh…

But one thing I did do, when writing ‘Richard’ was to leave the other real characters out. It’s just me and him. Because in the end, the book is as much about me, as it is him. Maybe even more so?

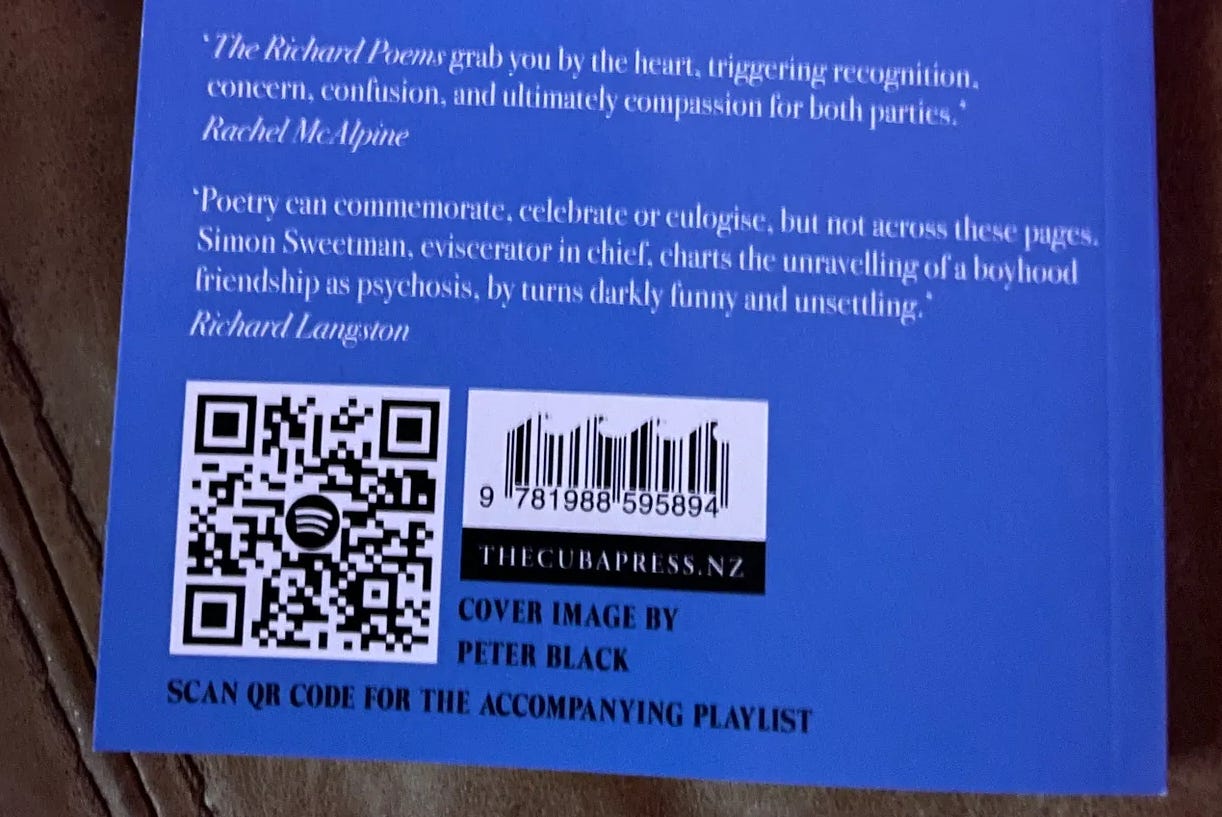

That’s why I loved the back-cover quotes from Richard Langston and Rachel McAlpine so much; they understood my assignment. Rachel even suggested compassion “for both parties”, which I had hoped for in the writing — absolutely.

What I stopped myself from doing was talking in any great detail about members of my family, members of Richard’s family, and other friends. (The idea of other friends is referenced, ‘they’ are there in theory, but no names or identifiers are given — and, similarly, I mentioned he had a mum and dad, they cameo in a couple of poems, but they’re generic; they could be anyone). I might have thrown him under the bus to write my book, but I wasn’t throwing anyone else — the only other person up for examination is me.

The book is a two-hander then, like a set of dialogues — I’m just writing both parties, or like a play where there are only two characters to bounce the action between.

There are other poems and stories where I mention real people, and the rule of thumb, usually, is that it’s observation — and any specificity is to make something so detailed and real and singular seem more universal. Like my silly ramble about Athol Guy from The Seekers:

It started off as poem —

— and then became the story linked up above. Both use most of the same words, in mostly the same order, and really Athol Guy is irrelevant in both cases, it’s about the absurdity of me being a 13 year old backstage at a gig (I never wanted to be at), and how I could not care to be there (backstage), and how that’s the feeling I’ve had ever since — regardless of who the act might be. It’s funny for a couple of reasons (I hope) including the fact that I’m now about the age that Athol Guy was when I met him, briefly. He seemed like a really old man! (I feel like that myself some days now).

I also try to make myself look bad, or silly, or at the least equally ‘daft’ for want of a word, or, you know, not the person that has any sort of upper hand.

Recently, I’ve written two things that have challenged all of this, two things where I have felt a tiny bit strange writing about real people, but that feeling has been what has compelled me to follow through.

In the weekend, I wrote a poem about the amazing singer/songwriter Alejandro Escovedo. I love his work. And I had a wonderful conversation over the phone with him which appeared as an episode of my old podcast:

Sweetman Podcast: Episode 159 - Alejandro Escovedo

By the time of the gig — which I loved — I was a bit drunk, from a wedding I’d been at that day. Happy-drunk, with-it drunk, engaged-drunk, but still drunk. Which musta stood out like a dog’s balls to a recovering addict.

Stubs: # 223 – Alejandro Escovedo, Wellington, 2019

Anyway, something about the weekend just been — listening to his music, going for a walk, being in a space where my mind was suddenly clear — brought back the very real feeling I had when I realised he was staring straight through me, and wanted our conversation over. (In the end it was another version of the backstage feeling; the “Being Backstage” story). I wrote the poem in my head, then put it down on the screen. Felt bad about it. Felt great about it too. Meant him no harm of course, and meant only to show a version of me that was a bit of a dumbass; caught in a bit of a bad luck moment too, if anything.

The other example I have, and I’ll close with this, is a very dark vignette. I don’t feel great about this, but I also think it hits fucking hard. And that, I guess it what happens with “real people” stories:

Short Story: Michael

I want to push to write darker, weirder, deeper — and to go deeper in very few words. So in that regard at least, I think ‘Michael’ is a success of some kind. And my apologies for no trigger warnings, it’s not that I don’t believe in them, it’s just that I forget. I feel like writing is its own trigger warning, and to give warnings is to sometimes offer essentially a ‘spoiler’.

So that’s my thoughts — for now, at least — on writing about real people. I wonder what you think?