Tone of Voice in the Short Stories of Langston Hughes

Wednesday is about books and/or writing. Today it's both. Here's an academic essay I wrote recently about the short stories of Langston Hughes

Hughes Is Writing, But Who Is Speaking? Tone of Voice in the Short Stories of Langston Hughes

“A certain level of shield — we could call it masculinity, or coolness: the idea of cool, the mere ideal of cool was invented by Black people to protect themselves in this country […] But we made it sexy…We can take dark emotion and make that cool, too.” —

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson [speaking specifically about Prince in 2024][i]

The idea of shields, of masks, is common to the various representations of the Black experience in song, film, and literature. An idea of coolness appears too, of being able to handle. Do we project that, to some degree, because of white guilt? Do Black actors, artists and authors embrace it as part of storied self-preservation? The concepts of ‘blending’ and ‘passing’ suggest that the Black American has no race or must strip their race/is able to merge with the White race; expected. Better yet, may even ‘pass’ as being White, as fitting in.

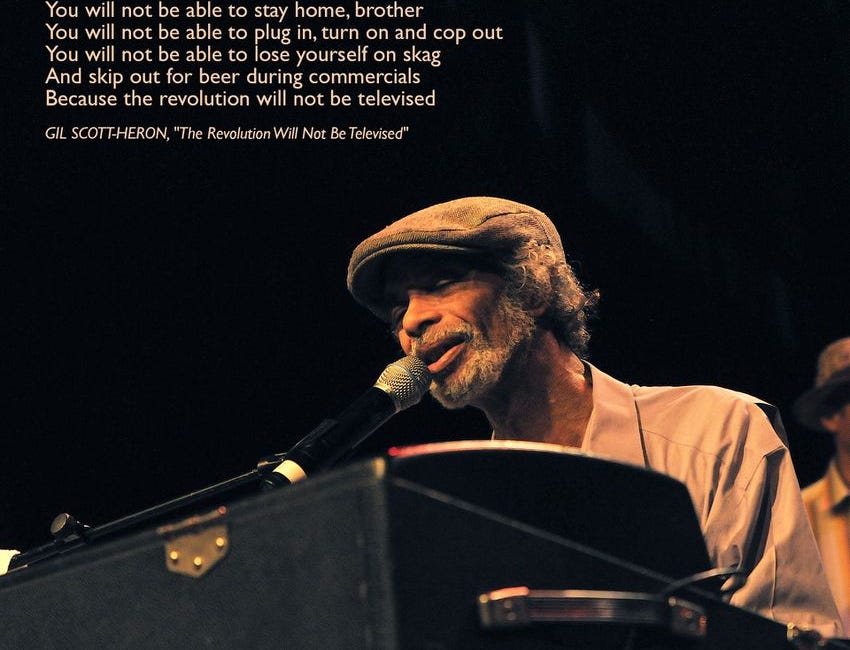

The writer [James Mercer] Langston Hughes, innovator of jazz poetry, leader of the Harlem Renaissance, sometimes referred to as the Negro Poet Laureate, or Poet Laureate of Harlem, saw Walt Whitman as a poetry hero rather than a ‘White’ poetry hero. He saw the way Whitman used the ‘I’ for both himself, and as the stand in for all (white)people in his landmark poem, The Song of Myself, and he used the same technique, the same approach in his own verse, The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Where Whitman was everyone and everywhere and all at once, in his sonorous claims that he may very well contradict himself since he contains multitudes[ii] — his poem a voice for all of America (which is to say ‘White’ America) — Hughes’ poem in response takes up the voice for only African Americans. A weary voice.[iii] We feel that right from the title, The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Whitman’s song of himself is the song of a projected ‘everyone’, where Hughes uses his ‘I’ to speak for the Negro race, and the reason they speak of rivers is because Black women were not allowed in hospitals to give birth. The poem has a sing-song spiritual quality to it[iv], a mid-point between the coded slave-escape Christian hymn Swing Lo, Sweet Chariot and the Sam Cooke-penned civil rights-era anthem, A Change Is Gonna Come (with its opening lyric echoing Hughes’ sentiment, “I was born by the river in a little tent” and then “just like the river, I’ve been running ever since”)[v] and Hughes is harking back to earlier African American spirituals, while going on to influence not only Cooke, but also Gil Scott-Heron:

Because I always feel like running

Not away, because there is no such place

Because, if there was I would have found it by now

Because it's easier to run[vi]

Hughes’ weary voice informs The Weary Blues, his first volume of poetry.[vii] The Negro Speaks of Rivers is dedicated to W.E.B. Du Bois, sociologist, historian, writer, and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909.[viii]

An acknowledgment of the work done by Du Bois, of an ally in a movement. In the poem, The South, Hughes anthropomorphises the geographic location of the title. He admires the beauty of the place, but concludes, “I, who am black, would love her/But she spits in my face./And I, who am black/Would give her many rare gifts/But she turns her back upon me.” He then seeks the North (“The cold-faced North”) believing her to be a “a kinder mistress,/And in her house my children/may escape the spell of the South”.[ix] Gil Scott-Heron uses this as the springboard for similar thought in his 1970 poem Paint It Black recorded for his debut album, Small Talk At 125th And Lenox[x]

Picture a man of nearly thirty

Who seems twice as old, with clothes, torn and dirty

Give him a job, shining shoes

Or cleaning out toilets with bus station crews

Give him six children with nothing to eat

Expose them to life, on a ghetto street

Tie an old rag to his wife's head

And have her pregnant and lying in bed

Stuff them all in a Harlem house

And then tell them how bout things are down South[xi]

Randy Newman explores it also in his 1974 song, Rednecks, where he talks about the North setting the negro free — and then lists all of the place (housing projects, dedicated spaces) where back people have been “free to be put in a cage”.[xii] (Harlem is one of the places named).

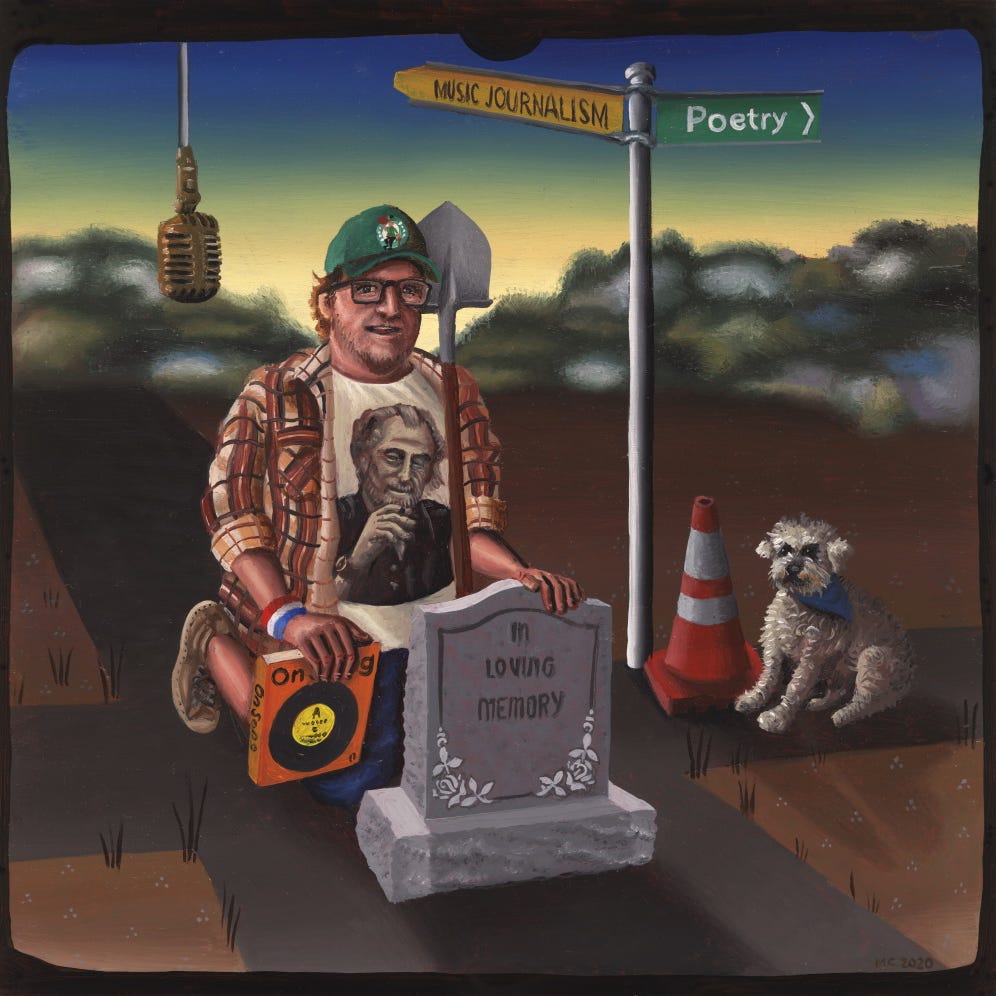

The poetry of Hughes, and the voice he uses, an influential ‘tone’ across the Harlem Renaissance, with its callbacks to the Civil War era, and the displacement of the black race, forced into and peripatetic across the North, is journalistic. The ‘I’ voice is clearly an ‘I’ on behalf, an ‘I’ that speaks for race, and would go on to inform the socially conscience musical work of Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, and Gil Scott-Heron. It would also be behind so much of the poetry that Gil Scott-Heron put on the page or took to the stage, that which he published, and later turned into music. The voice that Hughes created was one of authority, a stoicism, confident while weary, strong and aware, and rooted in the recent history, mindful always to address the history; it is noticeably clear where Hughes is in all of this — his voice the clarion. To Hughes there was no sense in being a poet only, despite wanting to see Whitman as poet rather than White poet. For Hughes though to only be a poet and not a Black poet, well, that would be turning his back on his race. He argues this in his essay, The Negro Artist and The Racial Mountain[xiii] — the hill to climb is one that requires the strength that comes from reaching inward, from digging deep, from carrying, and being carried by the weight of ownership of self. The acknowledgment of where he had come from is the acknowledgement of who he (now) is.

But there is something different that happens in the short stories. Hughes is still a Black writer. He carries to this role the weight of his name, a name made through being a poet before publishing stories. He brings with him the legacy, that sense of his own history and culture explored through poetry. It sits inside the words of his short stories, with the writer careful not to fully ‘out’ that voice, but aware that his audience too will know that it is there. I like to think that Hughes found a way to hang white people with their own words. The pun is most certainly intended, but if that seems too brash, then perhaps it could be said that where the poems were all about the ‘Black fight’ then the stories examine the ‘White flight’[xiv]; two different forms through which to explore the two different responses of the two different races that made and divided America.

In the children’s book, There Was A Party For Langston, Jason Reynolds writes, “[Langston] could make the word ‘America’ look like two friends making pinky promises, to be cool, to be true.” [xv] There is that notion of making things ‘cool.’ Were the two friends making pinky promises truly friends though? And what conviction was there behind the promises? Does a pinky promise last, or even mean anything for any longer than the moment in which it occurs? There is something akin to Stockholm Syndrome in the stories Hughes wrote for his debut collection, The Ways of White Folks.[xvi] Poems from The Weary Blues trudge with the weight of history, stories in The Ways of White Folks skip with a deceptive lightness, as we read of cultural tourism where the White characters are concerned (‘The Blues I’m Playing’, ‘Slave On The Block’) and watch the tone move towards irony to achieve satire as the White women forcing the classical world of the piano on a Black student in ‘The Blues I’m Playing’ has no facility for the soul and heft that is eventually put behind the performance so therefore dismisses it due to not understanding it; as the White characters in Slave On The Block, all but unctuously declare their reverence for the African-American race.

Gone is the ‘I’ of the poetry, which owns the words, whether collectively on behalf of his race, or personally from his own experience (or of course both). In place we have the free and indirect speech of a narrator whose eye of God is jaundiced by unknowing or prejudice, or at the least a profound lack of self-awareness. But by removing the self, by letting the words float in space, this is how Hughes lets the White race ‘hang’ — dangling them by their hypocrisy, their dominance, their smug level of personal pride on display against a complete covering of the fact that such behaviour only promotes and continues power and class struggles. ‘Slave On The Block’ opens with the white characters Michael and Anne Carraway being described as being “people who went in for Negroes,” though not in any “philanthropic sort of way.” And then the the dismissive generalisation that there was no point in “helping a race that was already too charming and naïve and lovely for words.”[xvii] The Carraways would rather use their white privilege (money, security, social standing) to pay the doorman a tip at the Harlem nightclubs so they could gain access to the culture they are so sure they adore.[xviii]

This is used to back up the insinuation that by essentially purchasing access to the art they are artists themselves; appreciators on a level where they are part of the spectacle after buying and declaring it a spectacle:

“So they went in for the Art of Negroes—the dancing that had such jungle life about it, the songs that were so simple and fervent, the poetry that was so direct, so real. They never tried to influence that art, they only bought it and raved over it, and copied it. For they were artists, too”.[xix]

It allows the Carraways, as their name might suggest, to get carried away with their reverence for the Black race, which only makes them look bad; they are the collectors with an ether rag, working in the hope to pin the specimen down long enough to secure inside a glass cage for display. That weight of Hughes’ own legacy is slyly referenced. In creating satire, the writer usually has some personal smirk around the skewering, and you can feel it when Hughes puts words onto the narrator who describes the Carraways as knowing that “the art of Negroes” contained a “poetry that was so direct, so real.”[xx] From naïve admiration to insidious objectification, Hughes is still moving the lines with the economy of his poetry but utilising a whole new voice. Even the title of the collection, and the grouping of the stories, interconnected by theme/s, Hughes allows the words to do the work, and for his earlier work as poet and essayist that shaped a movement, that reflected a community, to stand now as passive observer. He is the journalist-anthropologist in his studying of the ways of white folks — so important there’s no second ‘the’ in the title. For this is a collection of observations. One White woman’s ‘white flight’ is to move across town to a new apartment as a way of dealing — by not dealing — with the complex feelings when Miss Briggs in the story ‘Little Dog’ develops complicated feelings for the janitor in her building when she sees his tenderness towards the new pet dog. And her? Flips, her dog, is tiny — and white. Janitor Joe is physically imposing — and black. Hughes has fun layering this through. And when Miss Briggs cannot cope with the attraction, she starts to feel she shuts it off by changing locations. A literal ‘out of sight, out of mind.’[2][xxi] This is Hughes saying not all White people in a way that allows the very general to become very specific. In the story ‘Poor Little Black Fellow’, adopted Arnie is embraced by an upper-class White couple, but this is not enough for Arnie in terms of connection. Something is lost. His heritage. His understanding of where he came from. He has no rivers to speak of, at least not that he is able to become aware of, and this is his ultimate feeling of loss.[xxii] If the book was called The Ways of The White Folks it would be to point a finger, instead, through free and indirect speech, and by calling it The Ways of White Folks, and by using deep satire as his form of humour, to cope as well as to criticise, Hughes, in the end, may point many fingers. His overall tone is less accusatory, more quizzical. How did it get to this? Hughes has his own lived experience. And with that knowledge he presents a set of scenarios that are as true as any journalism, that are the social (and anti-social) proof of the neighbourhood he wrote into place by allowing the judgment to sit with the reader rather than to come from the writer. And yes, there is dark emotion, and shield, and there are moments when Hughes makes that ‘cool’. There are also moments where he allows the shield to filter the experience so that his tone is more opaque than it ever was in the poetry that gave him his platform.

Langston Hughes was always writing, but sometimes it was not him we were hearing from. We felt him, always. Throughout his various writings in different formats. But by allowing White people to hang by, in, and on their own words — given voice via a narrator using free and indirect discourse — Hughes was able to layer levity and grief into the folds of his short stories. It is this technique, this feel and flow, that allows them to still startle and surprise close to a full century later. Some of the terms may be outmoded now, some of the change that he and Sam Cooke both hoped would come may, on some level, have arrived. But to read these stories is to feel the very visceral nature of events, even through, if not because of, such sly detachment.

Bibliography:

Articles:

Hughes, Langston, ‘The Negro Artist and The Racial Mountain’, The Nation, June 23, 1926

Weiss, Sasha, ‘The Prince We Never Knew’, The New York Times, September 8, 2024

Books:

Hughes, Langston: The Weary Blues, Mint Editions, 2023

(first published 1926, Knopf)

Not Without Laughter, Payback Press, 1998

(first published 1930)

The Ways of White Folks, Vintage, 1990

(first published 1934)

Magill, Frank N. (ed): Masterpieces of African-American Literature, HarperCollins, 1992

Reynolds, Jason: There Was A Party For Langston, Atheneum/Cailtyn Dloughy Books, 2023

Young, Kevin (ed): African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song, The Library of America, 2020

Compact Disc:

Various Artists, Voices of Black America: Historical Recordings of Speeches, Poetry, Humor and Drama 1909-1947, Naxos, 2002

Gil Scott-Heron, Small Talk At 125th And Lennon, Flying Dutchman/RCA, 1970

Randy Newman, Good Old Boys, Reprise, 1974

[i] Sasha Weiss, The Prince We Never Knew, The New York Times, September 8, 2024

[ii] Walt Whitman, Song of Myself, 1855

[iii] Robert Niemi, The Poetry of Langston Hughes, Masterpieces of African-American Literature, P.413

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Sam Cooke, A Change Is Gonna Come, RCA, 1964

[vi] Gil Scott-Heron and Jamie xx, Running (We’re New Here) XL Studio, 2011

[vii] Langston Hughes, The Weary Blue, 1926

[viii] Ibid, P. 63

[ix] Ibid. Pp67-68

[x] Gil Scott-Heron, Small Talk At 125th And Lennox, Flying Dutchman/RCA, 1970

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Randy Newman, Good Old Boys, Reprise, 1974

[xiii] Langston Hughes, ‘The Negro Artist and The Racial Mountain’, The Nation, 1926

[xiv] Jeff Cupp, The Stories of Langston Hughes, Masterpieces of African-American Literature, P.539

[xv] Jason Reynolds, There Was A Patty For Langston, 2023

[xvi] Langston Hughes, The Ways of White Folks, 1934

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Ibid

[xix] Ibid

[xx] Ibid

[xxi] Ibid

[xxii] Ibid

See also: