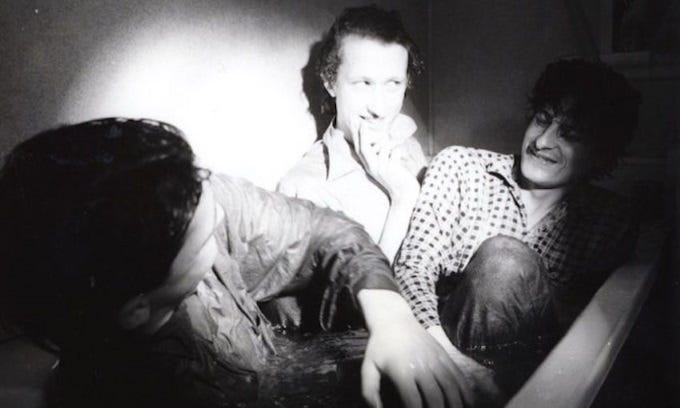

Remembering Hamish Kilgour

Wednesday is about books, and writing. Today it's the words of Hamish Kilgour - reshared here with his earlier permission. R.I.P.

Very sad news about the disappearance and now death of Hamish Kilgour.

I wrote a wee eulogy piece there in that link, as I do when the death of someone important has an impact on me, when I want to speak about their work, or a connect we had - maybe through the work, maybe through meeting personally. In the case of Hamish, it was both.

I sometimes think there’s no finer music on this planet than what he and brother David achieved as two-thirds of The Clean. The mighty Clean. The bruised and beautiful Clean. Bedsit champions of the world.

I met Hamish about three years ago. He had breezed through Wellington for a messy solo show. It didn’t really have a beginning or an end, but Hamish wasn’t quite feeling the set, so walked after a song or two; if you could even call them that. He stayed around all night though, and was on the stage at the very end, the venue trying to close for the night, his sticks and cymbals taken to stop him from hitting the drums, so he improvised with a couple of hardcover books from the stage backdrop.

He had suggested we record an interview for my podcast after the show, so I held on for as long as I could, sometime around 1am it was clear he wasn’t going to talk that night, but he told me to meet him bright and early for breakfast the next day. I did. And it was clear that Kilgour had not slept, he was proud of his time wandering the night, he had bought some food for a couple of people sleeping rough, he had made a necklace down by the water, he was enjoying a very early morning cocktail.

It was also clear that he was nervous about chatting for the record, and had invited backup in the form of his opening act, various bandmembers and a couple of friends from the past. So we sat and waited them out. Eventually, in the middle of the day we recorded a conversation leaning against a wall, with music from tradies and background hammering and smashing lending a flavour to the chat that seemed in keeping.

It was a good get. And yet it made no real sense. It was a 35 minute conversation that was essentially one giant run-on sentence. It was a perfect sprawling mess. Just like when Hamish sat behind a kit, or strummed a guitar, never letting his technical limitations slow him, always allowing them to inform the sound and vibe and presentation.

He was wild. And gentle. Because we are never just one thing. We are always two people. At the very least.

My first interactions with Hamish had happened a decade before that. And only online. I was writing about Anything Could Happen for my book, On Song.

I had emailed both the Kilgours with some questions - very simple questions around the creation of the song. It’s a short, deceptively simple song. And David replied with short, deceptively simple answers to the generic question-line.

Hamish asked if it would be okay for him to reply in a bigger paragraph.

Of couse!

What turned up in my Facebook messenger feed I can only describe as being a single, punctuation-less rant; an unweildy paragraph that seemed to simultaneously answer and ignore all of my questions. It was a potted history of the band, but it wasn’t. It was Hamish’s philosophy. But it also wasn’t really.

But it felt like a love letter to a creative from a creative - and by that I don’t mean to me, from Hamish, rather to Hamish from himself. It was beautiful. I was sure of that. And I felt honoured in receiving it. I felt a little like Jack Kerouac’s publisher might have felt when the original type-scroll of On The Road arrived. Just one giant, long screed. Messy and beautiful. I used what I needed for the chapter in the book, but wanted to memorialise the words, so I asked Hamish if he’d mind if I tidied it up into a user-friendly reader-shape and published it on my blog. He was very happy. He even supplied a title for me.

The Poppies Want To Grow A Little Taller

He was thrilled when it first went out to the world on my blog on Stuff, and then later republished on my Off The Tracks site. So I want to share it again, knowing it has Hamish’s blessing.

You’ll read plenty of fine tributes no doubt. But it’s my great honour to be able to share (again) words from the man himself.

And R.I.P. Hamish. The rest of the words, below, are all from Hamish Kilgour:

The lyrical base for the song came out of an experience where I was recommended by my Christchurch uncle to go see a pal of his in Dunedin where we were living who ran a commercial graphic art business. I was probably “between engagements”, my uncle knew I was very keen on art and I took my drawings and paintings down to see this guy. He looked at my stuff and pronounced that what I did had no commercial usage and I should get myself together if I was to even function in the NZ work-a-day world. Ah yes, fuck you very much.

It was funny cos a current girlfriend was discovered by me on my visit working in this same company for this asshole and she hated the job intensely. She was a trained graphic artist. He’s the doctor who points me to a junkyard – that’s my Dylan reference – and she’s my junkyard angel. The whole song is a nod to Bob, with the imagery of empty doorways and highways. As a teen I had devoured all of Jack Kerouac’s writing, gone hitchhiking around New Zealand and hung out around the fringes and insides of Kiwi hippie surf and glam counterculture. I had experienced radical young schoolteachers out of Christchurch in a small country high school at cheviot in North Canterbury. We had a cool art teacher, we did photography, sculptures for a small ceramic kiln and we’d be listening to radical socialist schoolteachers talking about Malthus, playing us Revolution No. 9, digging Hendrix, Joe Cocker, The Who, The Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Byrds, Jim Morrison’s lyrics…etc.

There was a secondary school magazine called Affairs which was full of progressive stuff, the Little Red Schoolbook and wild Canterbury university capping magazines…we would go down to Christchurch for fixes of music and books and street fashion and always come back with some new thing. Christchurch seemed way more vibrant to my young eyes then, it was a different place. It seemed much more urbane and urban before they started tearing down all the Victorian and Edwardian buildings, but most importantly fun and free and easy full of small cool shops, alleyways and alcoves.

I digress, but all this fed into my consciousness…

I went to Otago University (1975-77) and got a BA with a double major in English and History. I also delved into political science, experimental American fiction and medieval history and literature including Old English and medieval passion plays. I also dove into decadent French literature and esoteric thinkers and philosophers.

So punk starts hitting on 77 after we had been into the Velvet Underground, John Cale, Neil Young and of course Dylan and The Stones (I was an early Stones freak) and don’t forget Bowie, Bolan and the Hoople. The Ramones and their dumbed down minimalism immediately appealed. Our first attempts at songwriting were reductive attempts at matching our primitive abilities as players. I deliberately tried to write simplistically and obtusely. I had been smitten by Arthur Lee and his writing for Love. I took my first acid trip around this time.

We had also gone deep into American psychedelia – and listened to Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Strange imagery with open-ended meanings where the listener could play with the lyrical ideas and extract sometimes several meanings from lines much like Dylan, complexity and simplicity in one rocking and rollin’ ball.

Anything Could Happen was an amped-up rocker when we first performed it. Often David would come up with riffs and I would match with lyrics and we would jam up or write songs whilst rehearsing. Sometimes lyric catchphrases or ideas would come afterwards for me, walking the streets and hills of Dunedin and we would figure them out together – it was pretty exciting because we were trying to write songs and playing with structure. I wrote some laughable crap at this point in time but it was all self taught experimentation, doing it for ourselves and, for me, free of institutional learning.

Anything Could Happen is a pretty simple song. I think my reading of Kerouac and Ginsberg and Burroughs informed the optimistic, Buddhistic chorus with the verses essentially being negative, echoing confusing social messages and behaviour, hypocrisy and the ridiculous weight given to so called authority. Alienation and despair. We were reacting to our parents’ conservative ideology and mindset and conservative New Zealand culture. And Dunedin has a particular strain of Presbyterian stoic Scottish repression and conformity that spins into aggression, dogmatic moralism and drinking and drug abuse as the only license to be able to let go and be a bit free.

I’m glad I have Irish and French blood to counter the dour highland Scots bit. I like the image of the doctor being someone you go to “fix” yourself cos you are unwell. You need a drug to help you cope but then you discover that he is the king of the capitalist junkies and he has to have his fix first before it’s your turn. The supposed norms of society are f**ked up. It’s a nod to Lou Reed’s I’m Waiting For The Man: gives you free taste but you’ve always got to wait. In this case I was sent to the doctor who is supposed to help –but he’s a f**ked-up junkie himself. This is also based on experiencing a bad doctor who was feeding people drugs with no moral discretion or care for her patients back in North Canterbury in the early 70s.

The Big City is Auckland, which was the biggest city I had experienced. I actually arrived in Auckland in a white Rolls-Royce with my cousin in early 1976 (Xmas hols). We were hitching out of Tauranga and I was standing on the road eating a breakfast out of a box of muesli when the driver of the Rolls picked us up. He was working for some rich dude in Auckland. That summer in Auckland we stayed in a flat with a Christchurch Maori friend of my cousin’s who was working at a working man’s Queen Street bar selling Lion Red to customers. He lived above a group of hipster-junkies one of whom had a shaven head and was dying of cancer. You could go to the Globe tavern and see early Hello Sailor and listen to a jukebox with Roxy Music and the Grateful Dead side-by-side: Neil Young Be Bop Deluxe, Little Feat, Bryan Ferry, The Stones…free concerts in Albert Park. Beautiful old Auckland with its arcades and cool architecture before the gutting in the 80s.

I can remember walking through The Domain and down through Parnell in bare feet. Something I wouldn’t have done in 1979 with the heyday of the bootboys, urban soullessness and the ever-present possibility of violence. New Zealand seemed a kind of safe place but wanton violence was always a possibility around any corner. New Zealand was definitely a more easy-going egalitarian place in the 70s; yuppiedom hadn’t arrived, youth culture was less divisive, working class kids went to university, nobody had much money, everything was cheaper. And it was not so much about materialist wealth/greed and trying to hold onto what you had grubbed for, there was a better sense of community, easy play and humour. Things started changing after the oil shocks and the lack of employment that I experienced as soon as I pooped out of university – it’s weird but the things that informed NZ punk and the social tension are all here today staring at us in the face. Except, substitute underclass for working class. And more extreme wealth inequality.

And its funny but I came across an old university English lecture notebook of mine at me mum’s place and along with scrawled images and the current bands that I was besotted with was the word postmodernism with a question mark after it.

We were punks as it happened.

I had cut off my long hair super short, pierced my ear, distressed clothing bought in op shops – and tried to bleach my hair like Lou Reed’s in 1975. I had people yelling “deviant” at me and punching me in the stomach walking George Street late at night. The V8 boys begat the bodgies who begat the bogans and so it goes.

So anything could and can happen – it’s how you deal with the reality of that moment: active rather than reactive. Still a good bit of advice to scribble on the inside of your head or write on your own notebook.

I still take notes on things that interest me. And I still have most of Bob Dylan’s best songs etched into my consciousness and I later came to appreciate his social-realist foil Phil Ochs. Plus even after the deluge of punk and new wave music that we devoured, we still listened to that old favourite Exile On Main Street in our touring van. The feel I was going for with Anything Could Happen in 1981 was a Highway 61/stones country feel. David and I had developed a great affection for the history of 20th Century folk, blues and country. After teaching ourselves how to be a punk band we sort of naturally gravitated to the music we had listened to leading up to punk. No pop, no style: we strictly roots.

I still feel we can wring meaning out of playing the song; every Clean version of one of our standards is never the same twice. Still look for that certain tempo and swing and it has a Velvet Underground-country feel for me when it’s working. We look to each other for the vibe and I still love it when David pulls something out of the hat on guitar as he always does.

I haven’t answered your questions directly. This has just been a ramble I work better that way.

This originally appeared here on Off The Tracks

Yes thank you simon

Beautiful Thankyou Simon.