Oscar Sweetman And The Shawshank Redemption

Monday is movies. Today - a classic, a favourite. Viewed through new eyes. (And with new eyes too).

We sat down to watch The Shawshank Redemption last night. The 1994 classic is almost a cliché – it ranks high on most lists. It’s a top prison film, a favourite Stephen King adaptation, it was the real kickstart to the idea that Morgan Freeman should narrate, well, everything…and it’s high on the list of movies that felt Oscar-worthy but never won. It was also named New Zealand’s favourite film on a poll a wee while back(Flicks.co.nz).

Some of this information has started to work against it over the years. But I’ve always been a fan.

I remember seeing it at the cinema with my friends at the time, Jay and Sarah. We’ve lost touch really, in that way you do. No falling out. But the years have moved us about the country and the world, and we might have ‘liked’ a few posts by each other on social media, but that’s about it over the last decade or so. I remember that first watch vividly. It was a small cinema, and someone left to go to the loo during it and the door remained open. It swung back, casting a light, and bit by bit some giggles moved through the room, punctuating one of the more serious scenes.

It was after I first watched it that I fully connected it up as a Stephen King story; it was probably right there in the credits and I’m not sure I knew that going in. Anyway, it was straight off to read Rita Hayworth and The Shawshank Redemption, the 130-page novella that gives us all the same details in such impressive economy; the written story that inspired a sweeping epic of a movie.

And I probably watched the film a few more times on VHS and then DVD. Sometime after that it became a TV staple, even. And I remember watching it a couple of years back on Christmas Day. Catching it by fluke when surfing terrestrial TV in an Airbnb.

Many years ago, there was a column in a music mag I read. (Many years ago, there was a thing called music magazines!) The column was called The Reaper (or maybe that was just the author’s nom-de-plume). Anyway, the idea was some Grim Reaper caricature would murder your darling/s. They would take a classic from pop culture, mostly an album or a movie, sometimes a book, and they would tear it to pieces, make a case for why it was actually a sloppy piece of shit. Not the absolute classic you figured. You were wrong. And they were right. And the writing was hilarious. A no-holds-barred attack on popularity. I used to love this column. Even (and maybe especially) when I did not agree.

The Shawshank Redemption was an early victim. Mocked for its mawkishness, and sent up for its sincerity, The Reaper was particularly brutal. And I took some of the comments on board as valid – there was certainly a huge suspension of disbelief needed for the storytelling to be allowed to shine. But that’s what you do with a good book or movie, you place some hope in it. And you allow it on its way.

I own the book that houses the novella (Different Seasons) and a standalone copy of Rita Hayworth and The Shawshank Redemption. I own Thomas Newman’s score on CD (it’s one of my absolute favourite movie scores – as I said right here). And I have a triple-DVD collector edition which also has the screenplay for the movie along with discs of extra commentaries and deleted scenes and some material I’ll likely never even see. So, you can see, I’m fully on board.

And to watch it again after a few years, was to let go of any of the things working against it. So what if it’s popular? That’s arguably a strength – maybe not always, but in this case, sure. Why not.

It’s also just a brilliant layering of a story, really quite shaggy dog until we get to the end, the ultimate payoff; a brilliant sealing of the deal of one of the great unlikely friendships. A validation. A valedictorian moment.

There’s a bit in the film that always gets me. It’s the saddest, most beautiful scene. And it was one of the bits The Reaper really blew chunks over – and that was funny, especially when I was in my late 20s or early 30s or whatever. But in the last decade or so particularly I’ve been so moved watching the story of Brooks Hatlen (played by James Whitmore).

Hatlen is the prison librarian. And midway through the film, he briefly takes over the narration. Brooks is granted his freedom from jail in his mid-70s, he’s been there for 50 years of a life sentence and it’s the only world he knows. His soul has been institutionalised. And in a sequence that feels like its own short film within the larger movie, Brooks writes to his friends back in prison to tell them about how he is coping in the outside world. He can’t keep up bagging groceries with his arthritis and lives in a boarding-room alone. The cars now dominate the streets, when he was a kid, he had a memory of seeing one or two. In one of the movie’s memorable lines, Brooks says, “The world went and got itself in a big damn hurry”. (I think about this line most weeks these days).

Brooks misses the bird he named Jake, he had nursed it to health from being an injured baby, then allowed it to fly off through the bars of the jail in a bit of (admittedly clunky) symbolism. But you’re allowed such clunky symbolism when you’ve bought in, when the movie or book has taken you by the hand to this point.

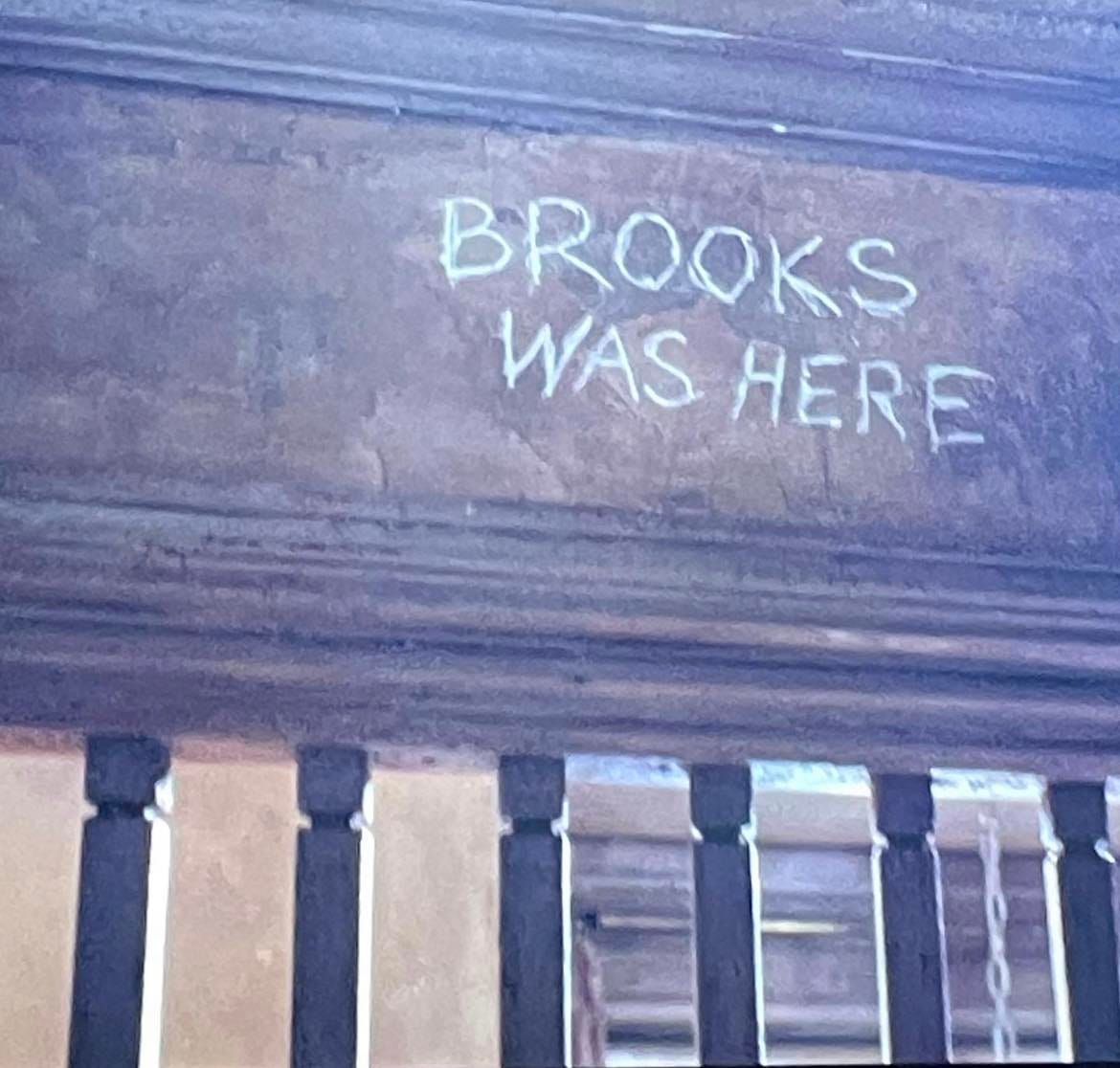

Hatlen climbs on a table to carve his name in the beam of the room where he was staying. Just like a prison signature. He writes Brooks Was Here, and then kicks the table out from under him and we see his shoes hanging still. In the mirror we can see his body stiffening.

It is brutal. And beautiful.

Frank Darabont understood King for the big screen arguably better than anyone (proving it again and again, The Green Mile, The Mist) and any little touches or changes he made to the stories he adapted were not only endorsed by King, the author has gone on record as saying he wishes he had thought of them.

Midway through last night’s screening, I said to Oscar, “oh yeah, I actually interviewed him”, as I pointed at the screen.

“What?” He said. Disbelieving. “You interviewed Andy Dufresne from The Shawshank Redemption”. Not quite, but close. I told him I’d interviewed the actor, Tim Robbins. Who, by the time I interviewed him, was not just an actor and a director, but also a musician (even if doesn’t need The Reaper to point out that strain of his career was never going to travel well).

I had genuinely forgotten (in a moment) talking to Tim Robbins. The Player, Dead Man Walking, Cadillac Man, Mystic River, Short Cuts. And of course Shawshank. There are others. But these are the movies I squeezed into our chat, ostensibly about music – and his patchwork, middle-of-the-road, poor-man’s-Dylan attempt at singer/songwriter-ing in a vaguely folk-inspired cosplay attempt.

Oscar said, “You mean to tell me you’ve known my whole life that you spoke to Andy Dufresne from the movie Shawshank Redemption and you’re just remembering to tell me now?!?”

“Yes”.

We watched the rest of the movie locked in a cuddle, the way we had when we last saw Stand By Me. They are similar movies/stories, connected not just by being in the same book, but by the way King writes male friendships. Oscar in fact pointed out this out to me too. He said, “King really does write about mates so well”.

Earlier in the day, Oscar had earned his blue belt at karate. And it had been emotional. I hugged him with tears in my eyes after his grading and he couldn’t believe I had cried. “Dad, you don’t cry. You never cry. Have you ever cried in my entire life?”

Oscar hadn’t quite crawled through 500 yards of shit-smelling foulness to get his blue belt. But in a metaphorical sense, we’ll have to let it stand. It wasn’t that I couldn’t even imagine, nor that I didn’t want to, it was that his effort had crystalised for me in that moment. The toughness he had shown to stick with it and complete the challenge, to get the reward.

And so we double-featured The Karate Kid (which we’ve both seen a bunch) and then Shawshank (which was Oscar’s first time), and we liked the connection between the two films. A connection we had made. One that might only make sense for us.

During the Brooks scene, which I had warned Oscar about and set up as the saddest moment, he started looking at my face closely. And he kept checking in as Brooks talked about wishing that Jake might show up when he fed the birds. As Brooks climbed onto the table to carve his name into boarding house eternity.

“Dad, you’re tearing up again!” He said, and then laughed. “That’s twice in the same day!”