On Monsters:

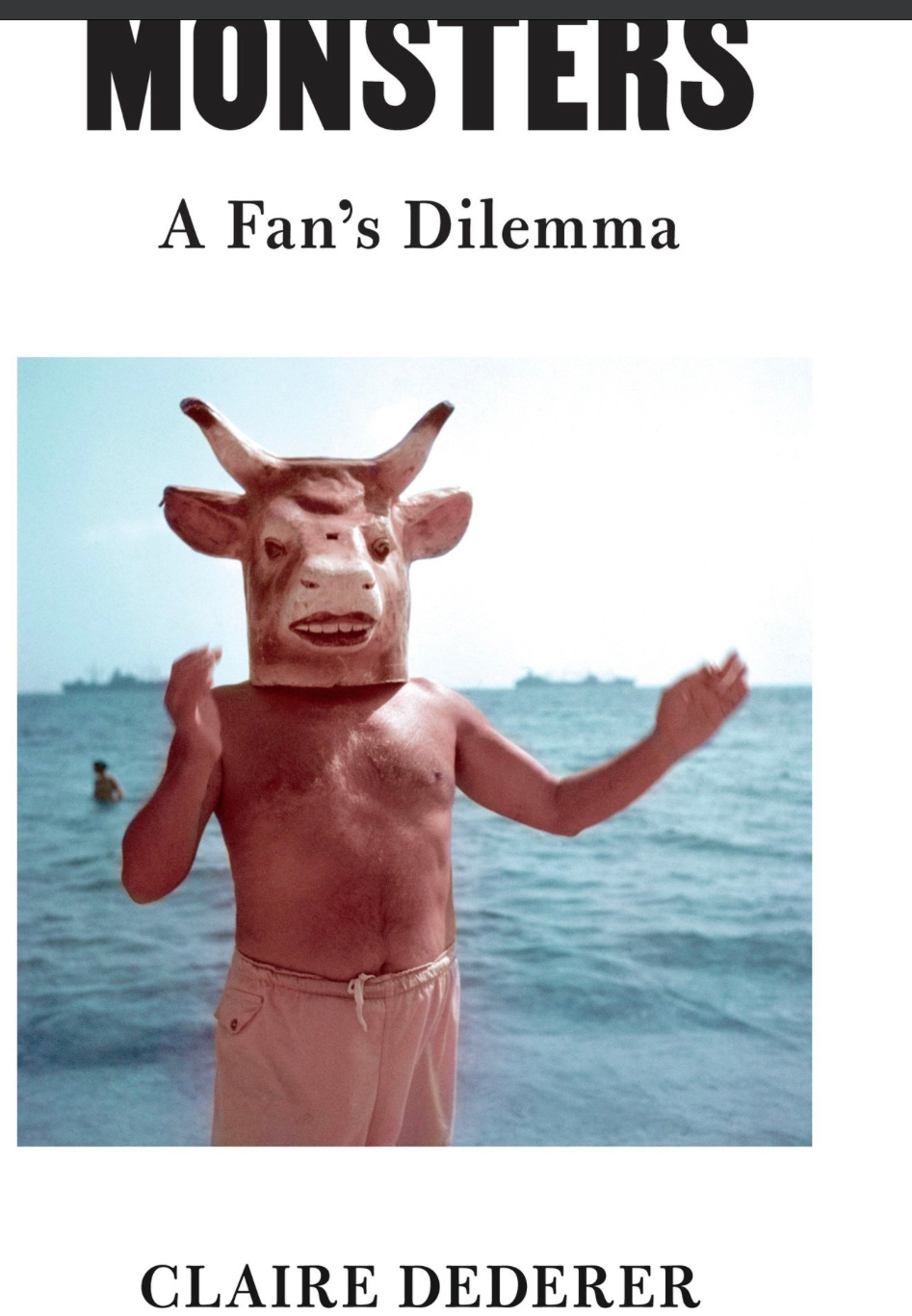

Wednesday is about books. And writing. Today, a new book “Monsters - A Fan’s Dilemma” on a topic for our times: Cancellation. And whether the work can stand.

The question used to be whether we could separate the art from the artist. Now it’s more around how we decide to do that. Is it best practice to listen to Michael Jackson’s music from when he was a member of the Jackson 5, rather than when he was building his own weird Disneyland bunker? Are we fine to enjoy that music and not think ever about his own e…