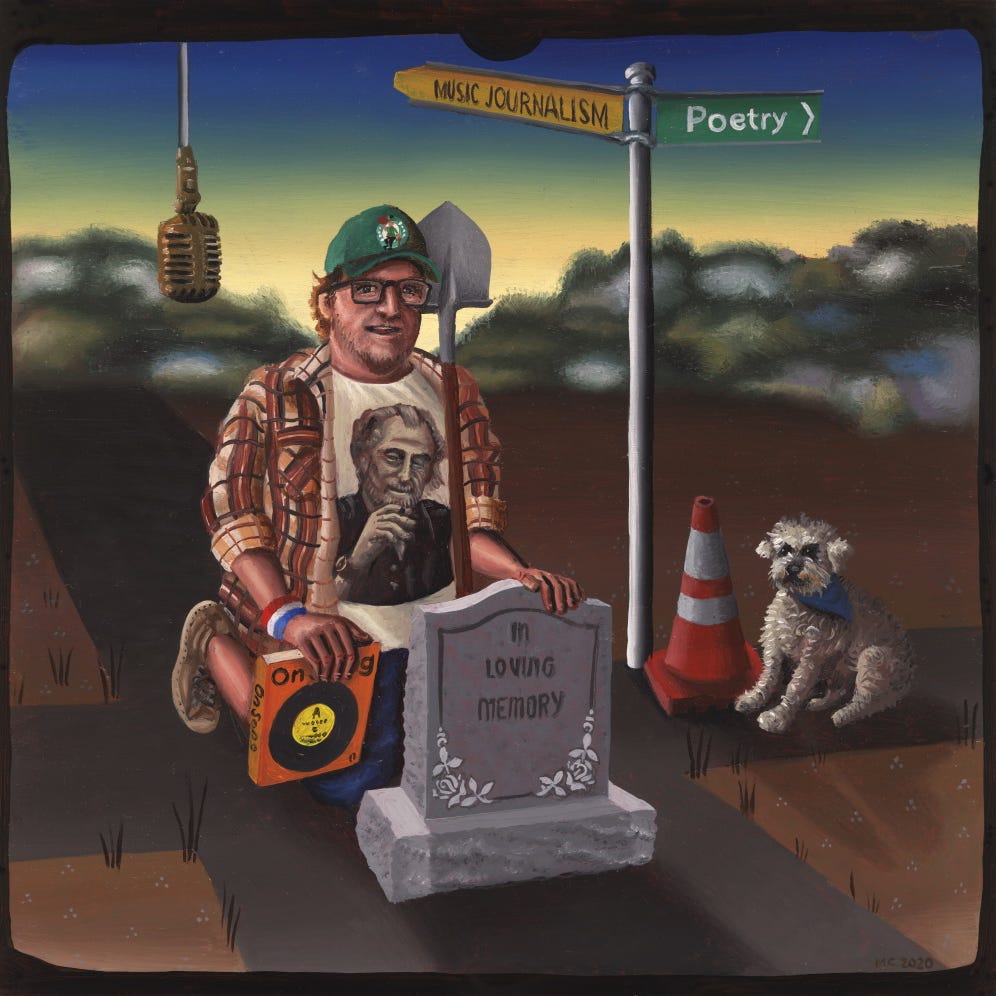

I mentioned to you, in another newsletter not so long ago, that I was having fun taking blog-posts that I’d written and turning them into poems. And that I was also taking poems and making them blog posts. I might add (or subtract) a word or several lines here and there but the gist of it was the same original piece, in terms of theme and concept – but now it reads all new, or at least different.

Also, c’mon, who are we kidding, poetry is not for everyone…or, at least, they don’t know it – so you have to sneak it in using other methods, present it in a different way. There’s poetry in all forms of writing.

Examples I’ve shared with you in slightly longer form include this piece about Tracy Chapman and this one about The Beastie Boys’ album Paul’s Boutique. I have this idea stewing away I guess that I could make a wee collection of these prose-poem things. They’re always about music but they’re just a short snapshot. A type of micro-blogging I suppose…

Today, I wanted to share a few more with you. Tell me what you think.

*

Some Of My Best Friends Have Been Songs

Walking home on stormy nights, to a house alone, back when you didn’t have music on your phone. I’d duck into a bus stop to change batteries(or the CDs) on the Discman. And I had no idea where I was going – but the songs were lighting the way, keeping me sane, keeping all else at bay. Paul Simon and Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell and Suzanne Vega, Leonard Cohen, Lou Reed, and there were others, many others. Some nights I had all the friends I’d ever need – and I always had good friends. But did you know that songs aren’t just friends to us – they are there for each other. Songs can make friends with other songs. We do it in the playlists we make, in the mixtapes we used to send – or made but could never send. But even if we couldn’t force connections the songs are out there doing it for themselves, connecting with each other. James Taylor singing about those lonely times when he could not find a friend. Carole King heard that, and you know what she wrote in return? You know. Or at the very least now you do. And next time you hear it, you’ll know one song was knocking on the door of the other. Answering the call. Music can be our very best friend. Songs grow stronger when there are other songs to connect with; we are the same. Any time of the year and all year around we all need friends for so many sunny days, the ones we hope will never end. That old north wind blowing, our friends helping us hold our heads together. Our favourite songs on, as we share our favourite stories. We won’t make it any other way.

When John Coltrane First Blew My Mind

When my brother returned from university with a John Coltrane CD it was like a special gift. He was out there discovering new worlds, the hunter-gatherer bringing the very best music back to Hawke’s Bay. That’s how it seemed. There was no other way to explain it at all. He was doing this very special work, in between classes and drinking and whatever else was going on. He was suddenly a god to me. Five years older, we had squabbled as kids, I must have been a ludicrous prospect at best. But when he left – and found some peace, if not quiet, we started to get on better than had ever been the case. We bonded over the music he returned with: Classic rock and jazz, names I knew and plenty I’d never heard of before. He’d demonstrate each album to me, picking out the very best songs. Led Zeppelin, The Doors, The Who, Lou Reed and Billy Joel (hey, there had to be a dud in there somewhere). But it was the jazz that really spun my world around. Miles Davis and Chet Baker, Tony Bennett and Sinatra – and then John Coltrane. That, particularly, was the one. Well, actually it was two albums that did it – The Stardust Session and A Love Supreme. Wow. When I heard the way that horn blew out from the speakers it was like hearing the most trusted voice, and a very special new language. I couldn’t speak it but I could listen – I was hanging from the idea of it, the very sound filled my soul, every part of it was magical. The beautiful thing – still – about hearing Coltrane play is it seems so perfect and yet also sounds unfinished. Which is to say that it feels like he still had things to say. There was more to come. Each piece of music feels so rich, so full but it is only part of a very deep conversation that Coltrane was having, with both himself and his audience – and of course with the musicians that swirled in and around with the sound that stirred up from his soul. It was a life-changer hearing his music. When I was 14 my brother bought me a John Coltrane t-shirt. I felt, for a year or so, like the coolest fucking person on this goddamn fucking planet.

One morning I sat and chatted on the phone with John S. Hall for over an hour. He is the lead singer and writer for the band King Missile. They are mostly known for their silly song, Detachable Penis. But that’s so unfair. They have many more silly songs they should be known for. Some version of King Missile was touring New Zealand. And I didn’t make it to the show in the end, despite being very excited about it (I later heard it was very poorly attended – that probably figures, but it still seemed sad to me). I did have a lovely chat with John S. Hall though. He is a published poet – he’s a lawyer too. His whole approach to King Missile is entirely about writing, not really about music at all. He basically pulled together a band around him because he needed something to break the tension – or boredom – around poetry readings. He wasn’t prepared to do half-hour poetry readings with his voice droning on, and so he masked this with cello and percussion and choppy rhythmic waves of guitar. We talked for ages – about all sorts of things. But it always came back to poetry and writing. If we talked about someone like Jonathan Richman, which we did (and Hall is a huge fan – and I am too) it was mostly about Jonathan’s songs and the writing. Sure, his delivery is crucial, his Sad Sam eyes and his melancholic stance set against the often optimistic lyrics – or sometimes it’s a sad story of a song delivered to a happy clip of guitar and drums. But to Hall it was always about the words and how they sounded, what they meant, how and when they were written – and this was the case as we talked about Dylan Thomas and Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot and then to Richman and Bob Dylan and The Flaming Lips and Lou Reed. At one point I told him that King Missile’s 1988 album titled “They” – their second record – just blew my teenage mind. I didn’t hear it until about 1990/1991 – and I had never heard anything like it. Sometimes when I listen to it now I still think there’s really nothing like it – those songs: Now, I’m Open, Mr. Johnson, She Had Nothing, He Needed, and at least another half dozen. But especially Haemophiliac of Love (“when I see you I bleed like a haemophiliac of love”) and If Only (“if only we could turn our heads into breads/we could slice ourselves up and make sandwiches…SANDWICHES!”) and Margaret’s Eyes. Which is just a spectacular pop song and then it has that dark turn – he talks about how grey Margaret’s eyes are – and lists a few things before saying they are greyer than the “the cigarette she puts out on me”. The Blood Song. When She Closed Her Eyes. The Box. WW3 Is A Giant Ice Cream Cone. I’m just naming song titles now – which is what I started doing during the interview. And I felt okay about that. And John S. Hall did too. But I didn’t ever print the interview. And I don’t feel okay about that. But that’s not because I worried about all the fan-boy gushing. It was, instead, because a burglar broke into our house – while we were still sleeping – and stole our wallets, and phones, our computers and I was unable to write the story up – I carried it in my head but didn’t feel able to hammer it out on the computer I borrowed to just get by. So I never wrote it up, and barely ever talked about it. I feel bad. John S. Hall is quite brilliant I think. And I reckon most people that have heard of him, or his band, wouldn’t know how serious he is about it all – and what a brilliant mind he has. And it was my job to share that news. And I failed. The burglar didn’t really make a mess at all. A clean operation. Fairly smooth. But there was a little tin of guitar picks I had and they were scattered everywhere. When the police came to dust for footsteps and fingerprints they found the tin behind a couch cushion and took photos and told me the burglar would have figured it a stash tin – would have been hoping for a good hit of something The police officer got a great boot imprint – and said they’d probably catch the crook as a result (and they did) It was super gutting to get robbed. But we were back up and on our feet – and able to leave our own boot prints about – within a day or two. Computers and phones via insurance, and some very kind people dropped off a couple of meals, someone else loaned me a computer straight away – and we got back the money the thieves spent on our cards too. But I always felt bad that they robbed me of the chance – in a way – of telling some of John S. Hall’s story. They didn’t rob me of the chance to speak to him though, and I can’t say I’ve been waiting all this time to talk about it in any way but here we are now, just as those guitar picks were scattered all about our floor in the very early hours of a Friday, not long after I talked to John S. Hall.

The Soap Opera of Fleetwood Mac

The soap-opera of Fleetwood Mac has had me hooked since I was about 10 or 12. There was a doco – a bit of late-night music-TV – that filled in all the blanks. I was already a fan, but I had no idea how the same band that sang Sara and Sweet Little Lies had jammed out an instrumental called Albatross. My brother recorded the documentary Fleetwood Mac at 21 and I watched it over and again. Until I could quote whole sections. Watched it like my own son would grow up to watch Peppa Pig and The Wiggles and then Doc McStuffins and now The Simpsons. Watched it the way people binge watch any of the TV they now consume. I’d get home from school and watch the same documentary about Fleetwood Mac over and again. Learning about the bit-part players – like Bobs Welch and Weston, and how sad to think of Bob Welch as any sort of bit-part only. For years I could only hear about albums like Penguin and Bare Trees and Future Games. These were hard to find – even though they were by my heroes. It was a mystery to me how to access some of the finest music I would go on to hear. So I’d cling to the clips and the funny, laidback things John McVie would say. And how defensive Stevie Nicks seemed when she’d talk about how Lindsey Buckingham would often say that he did his finest work working on some of her songs (even though Lindsey never did say it. Instead Lindsay talked about how frustrated he was with pressure and with the push and pull of various aspects that he could not control). The blanks were filled in for me – but it was still (mostly) about the music. The soap-opera is fascinating, that these fine musicians all fucked with each other’s feelings and fucked each other or fucked around on each other was somehow deeply compelling to me. Even at 12 or 13. I’d think about how they must have cared so deeply about the music – to keep it all going. And sure there are egos – and there was money and drugs and whatever else that becomes both the reason to keep going and the method of blurring anything else. And I have thought about all of that ever since. As I listen to the albums by Fleetwood Mac that other fans never bother with or might not even know about. And when I hear the biggest hits. Some of them I’m lucky enough to still hear as if for the first time. Others bug me a little due to overplay or because they were elevated in place of some of the true album-track stars. I can’t pick a favourite album or era – the blues band material is wonderful. Those “lost years” where the band was falling apart in some way for every album but was also as prolific as it was ever going to be. And the giant stadium rock’n’pop madness of Rumours and Tusk and Mirage and Tango In The Night. I went on to solo albums by not just Lindsey and Stevie – and their killer duo album that got them gig. I had VHS tapes of Christine McVie concerts and LPs by Mick Fleetwood and any guest appearances. And then the books and other video tapes and DVDs – stories and docos and so many hits compilations. I’d drive over to a mate’s house who lived half an hour away just so we could listen to our tapes of Fleetwood Mac, comparing whether live or studio versions were best. And yet I’ve never heard the story told better than on that dubbed VHS tape that my bro recorded late one Friday night. It packs so much in – 21 years in 51 minutes. We watched it first as a family. All of us hooked. All of us learning. I just took it to a whole other level. The way I did with a lot of music and memories and memorabilia and silly ephemera. These things meant the world to me. Some of them still do. And will forever. There are better bands than Fleetwood Mac but there are none that mean more to me in my lifetime.

The Impressions I Got: Discovering Curtis Mayfield at The End of a World

When I was lost – early 20s, no idea, never quite sure about what the plan was or where it was or if there even was one – I found the music of Curtis Mayfield. One of the greatest box-sets – a three-disc volume that goes through all the best of the Impressions material and on through the classic Superfly era and then to when he was cooking with doo-wop and those R’n’B roots and the funk was back on the back element. I could hear – straight away – what Prince and Lenny Kravitz and many others had taken from this music. How it must have flicked a switch or lit a fuse or whatever. And I recognised, on the first listen, that I’d heard so much of this already – in the music of Bob Marley and particularly his early Wailing Wailer. And then in actual samples from the best Beastie Boys record. When I was a teenager, I loved Bob Marley. And The Beastie Boys. It’s been so long since I was a teenager and only a few things remain from that period – I’m back loving basketball and horror films but I’ll always and forever love Bob Marley and The Beastie Boys. And that seems to me to sum up the span of Curtis Mayfield’s influence. To have been there ahead of Marley, to have sparked something for him, lit the path, provided one of the torches and to still be there for The Beasties too. I think about that Curtis Mayfield box-set all of the time. Think about it now, more than listen to it. I might listen to Al Green and Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye and Bill Withers and James Brown more than Curtis – but that time when I found Mayfield was deep. It’s deep with all the other names too. Sure. Of course. But there’s something in that soul-cry with Curtis. In those perfect guitar lines. Great hooks. Such grooves. And the heart and soul of the man – and his people – in those lyrics. Oh my. You could just cry to stop and think about it. My 21st was in the rearview mirror and I was so far from being in control of the wheel. And Curtis Mayfield was like a deity in my cruddy room. A lava lamp, incense, notebooks full of poems, ashtrays full of regrets. At the end of the 1990s Curtis Mayfield died. I was bereft. And no one in my immediate circle cared. We had a cheap version of the greatest hits, bought at the last minute for our New Year’s Eve party. So many of us were worried the computers would kill the world, the cars would stop, that life would end. There was a hell below. And we were all going to go. Bags packed. Time to Give It Up. Future Shock indeed. Curtis was gone. I felt like I’d always known him and was still just getting to know him. A day or two into the new millennium I’d make a call to the police to “help them with their inquiries”. We had a party that night after my fingerprints were put on file – I did some shots, we danced in the lounge, I slugged a few back, and shrugged it all off. When everyone left, I remember standing stunned in stillness. Listening over and over to I’m So Proud until the tears finally stopped.

Clint Mansell’s Music For Film Cuts Right To My Heart

Clint Mansell’s made some of the best music I’ve ever heard. Some of the greatest film cues and scores. And he was in the band Pop Will Eat Itself. I first really got to know his work when I watched Requiem For A Dream, a film that stays with me still. Its music, scored by Mansell and performed by the Kronos Quartet, is a character in the movie. And maybe I’ve listened to that score more than any other soundtrack to any other film. But there are more works of staggering beauty, of heart-breaking genius: The Fountain, The Wrestler, Moon, Black Swan, Noah and High-Rise. Even shitty films sound magical when Mansell paints the background sounds with his music brush. He scored one of the favourite episodes of Black Mirror. I didn’t think it was that special – but I sure did love the music. He has made beautiful music for films I might never even see (Loving Vincent, Out of Blue) and he has made not-very-good films better with his musical vision and ideas (Doom, Smokin’ Aces). Most recently he created a song-by-song cover of Lou Reed’s Berlin album. He’s reinvented it, all but rewritten it. The album was created out of his own grief. It’s amazing. And yes, I’ve reviewed it – but also, when I’m not listening to it I can’t stop thinking about it. This is what I want from music. Not all the time. Not every time, but this is how I chart the very best. The work made by the absolute greatest. It stays with you. It burns itself into your soul.

Walking In Memphis: Man It Sounds Good Tonight!

Marc Cohn singing Walking in Memphis is something I always believed in. And any time I hear it I can remember the first time I heard it – it didn’t really fit in with anything else I was listening to, or with much on the radio at the time; used to see it on the video-clip shows, late night music TV. It was strange and wonderful. There’s a power, a grace and a majesty in that song and I think it comes from walking so close to being hackneyed. But you feel the truth sneaking through between the lines. Everyone pegs it as an Elvis tribute because he sings about boarding the plane in his blue suede shoes, mentions the King and Graceland too – but it’s more about place than person, and if it’s about any one person at all it’s about Marc Cohn. This was him searching for a song, while searching for himself – or maybe that’s the other way around. He jumped a plane to Memphis to go and see and hear and feel the music his dad loved. He was also aware that he needed to write a good song. He hadn’t written anything that was up to much and he knew it – he was embarrassed to be on a publishing deal and with nothing to publish that felt right, felt good, felt real. But seeing Al Green in a church in the home of the blues and being invited up to sing with the woman that played the piano at the Hollywood Café every Friday night (Muriel Davis Wilkins) meant something, meant he had a song to sing and a reason to believe and a place to go, as well as somewhere he’d just been. I love the little hint of gospel, the hint of blues, the trace of soul – it’s a musical autobiography. And it always sat out on its own – a throwback and away from all time. It must have been hard to compete with this song, Marc Cohn wrote a few other gems but nobody seemed to care too much. Walking In Memphis is one of those songs…Okay, so it’s not quite Wichita Lineman. But then again, what is. And also, you know what, maybe one day it could be. It’s closer than most. It’s better than when you last heard it. Put on your blue suede shoes and board that plane for another trip.

How I Feel About Tall Dwarfs

When I first heard Tall Dwarfs I hadn’t heard very much like it (apart from The Beatles). And if that’s not entirely true it’s because we’re talking feelings, not facts. And that is an important distinction – and actually it’s the important truth when it comes to music. I wasn’t in on the ground floor either. I arrived late, crawling in through an open window halfway up their tower of songs, crashed the playdate they’d been having with lo-fi approximations of Beatles and Beach Boys melodies, merging samples and found sounds with noisy-pop perfection. Several of the duo’s best moments are only fragmentary; sketches of a moment – but that doesn’t make them less than great. Guided by their noise I started to look out for other things that had that feel and there are plenty – of course. Because they were liberally grabbing from so many open sources. They were happily nabbing ideas and repurposing them, applying just enough of their own special sauce so that you couldn’t ever imagine it existed in any other way – either previously or later on by anyone else. It’s perfectly believable to assume they invented everything in a back-shed with only the memories of a whole lot of great songs in their heads, doing it their way and only when and as it suited. And I sometimes think that not enough people know about them. Look, it totally spun my world. And sometimes it feels like it’s spinning still as a result of hearing “Stumpy” when I did; as a result of having “Throw A Sickie” on vinyl; as a result of that wonderful, silly, naughty earworm Gluey Gluey; as a result of “Weeville”, “Fork Songs” and “3EPs”. They have that thing where they’re my all-time favourite band in the world whenever I’m listening to them. And even when I’m not listening to them I’m thinking about them; thinking about how I should be listening to them. And that’s a fact. But it’s also exactly how I am feeling.

The Redemption of Rocket Queen

I loved Appetite for Destruction, right from first listen, such a visceral thrill. It was naughty as…well, naughty-as-fuck. We were probably too young to be listening to it but the unwritten, unspoken agreement seemed to be that if we didn’t copy the language – at least at home, anyway – it would be allowed. You might as well learn about the world somewhere and I learned a lot from listening to music. And now some 30 years on it’s the same with my son. He’s a couple of years younger than I was when I first listened to Guns n Roses (back when they first burst onto the scene) but a couple of years is nothing since in the 30 years from when this was first seen as controversial the world has been on a constant path of digital acceleration, thrilling at the start and now (mostly) devastating. I say to Oscar that he can listen away to Guns n Roses – he can even sing along to his heart’s content but he has to keep it as his secret music – let his mates discover it on their time, if at all. And just share it with me and some of the adults in his life and learn from it in whatever ways he can – musically and socially. And that’s going okay, so far, as he tries his best to play along on the drums to Sweet Child O’ Mine and air-guitars with a great deal more success to Nightrain and Mr Brownstone and Out Ta Get Me. He’s not yet started to care for Rocket Queen – despite me telling him that it is the hidden gem. And I respect the fuck out of him not listening to me on that point. He has his own favourites and that’s as it should be. But maybe one day he’ll see that Rocket Queen is the best and most important song of the lot. The epic closing statement that really ties the room together. If Appetite For Destruction is a book or a movie then Rocket Queen is the rug in the room where the final scene happens, the huge hug that pulls the war to pieces and brings the love back into the light. It’s getting harder in this day and age to excuse the sins of the lyrics and scripts and pages from the past when it should – if anything – be getting easier. Leave it to the past, that’s where it belongs and if you want to singalong or drag it with you like some long-lost baggage or a keepsake from a time you either remember or wish you were there for then that’s on you – if you know what to do, which is to own it so that it doesn’t own you. As a parent I listen to so much of Appetite for Destruction and nearly wince – most especially the use of the word ‘bitch’. Misogyny is never pretty, never funny, never gets easier or lighter or anything – it’s hard and it’s brutal and it’s tragic and embarrassing. And it’s easier to cope when listening to The Beastie Boys and seeing some aim at a maturity – eventually, some atonement, some softening (in the right way). But the bragging and desperation and anger and brittle sadness of the fronting from these sweaty, silly, drug-soaked buffoons is a tricky premise. Particularly when it rocks so hard and good and well – what they play is very, very good and what they say is so very, very bad… All of that falls away though, in some sense, when we get to the end of the record. “Listen”, I marvelled to Oscar, as it kicked off in the car the other day. The bass had just been mirroring the rhythm guitar as was the way in so much of the metal of the 1980s – buried or blurred, or both if you had the misfortune of replacing Cliff Burton. But on Rocket Queen there’s this killer-good bass riff, actual exploration. And they reckoned Steven Adler wasn’t much of a drummer but he swings his arse off on that record and plays what is supposed to be there. Never more so than on Rocket Queen – listen to it like it’s his final audition. He gets and deserves the job. (And this is his majesty. That he couldn’t keep the gig was the start of his tragedy). The guitars are great, they’re consistently great on this fine album of madness and mirth and barely repressed anger and giddy-wah dumb daddy-issues. And when the song starts it’s more of the same single-entendre innuendo – the whole album is basically “let’s do drugs and fuck” or even, “watch me do drugs and listen to me tell you about how good I am at fucking” – it’s as cartoon-evil as the (original) cover artwork, it’s rapey and dodgy and I honestly believe that even when I was 11 and 12 I saw it and heard as the way not to behave rather than any cool, clever blueprint for challenging authority. And in my moments when I worry that my son might be too young to hear it now in a world that moves just a bit too quick I remember the way Rocket Queen builds to its, er, climax… Axl Rose in increasing desperation holds his hand out in an offer of friendship, he’s stoic but utterly vulnerable – the eleven and a half songs ahead of Rocket Queen’s finale has all been the false-arrogance that’s been building to this:

Don’t ever leave me

and

Say you’ll always be there

and suddenly an album’s worth of extremely bad behaviour and putrid and puerile thought is not at all forgiven but it almost all washes away, is so obviously shown up as the overt front. Journeys. We’re all on them. Thrilling at the start – and now (mostly) devastating.

All I ever wanted

he finally admits – it took him about 53 minutes to arrive at this point, the place where he

strips it all down to basically all he actually wanted to say –

Was for you/To know that I care

Time Casts Its Spell: When Silver Springs Became The Secret Weapon It Had Always Threatened To Be

Stevie Nicks is told that her song Silver Springs won’t make the cut. The band is making Rumours which – we all know now – does pretty well. She leaves it in the vault for 20 years, takes it out, dusts it off, decides it’s time to bring it to life. She runs it by Lindsey. It’s got lyrics about how she would have loved him if he would only have let her. It’s got lyrics about how she’s going to follow him – and he won’t be able to escape the sound of her voice. That’s some incredible foreshadowing, especially since the tune is about to blow up, in the sense that it will become the set-closer, the encore, the new showcase. What would you say, if that was you? You’re there in the chair, confronted by a song you helped to make some 20 years earlier. So much water, but not many bridges. What would you say as you heard a version of your life handed back to you, completed by the commentary on what could have been, what should have been, and your own knowledge that you could have fought harder for the song to make the cut the first time? Chances are, you might not have instantly praised your own guitar tone, pointed out how pleased you were with the sound you gave to a song, as if it’s only just allowed to fly now because you were the one to give it wings. But Lindsey is a genius. And he’ll be the first to catch you up if you didn’t already know.

OST: A Good Score Is One of The First Things I’ll Always Notice About A Film

The music is almost always the first thing I notice about a film. It wasn’t always this way, and I can’t quite remember when it changed – obviously there are so many iconic themes we instantly think of from Star Wars and Jaws to ET and anything by Ennio Morricone, everything Quentin Tarantino chooses – which is different, that’s usually source-music though sometimes he picks an old song and uses it newly as score. Some time ago when I was 10 or 11 or 12 the music hit me and I’m glad it did. I felt no pain, only joy, and sorrow of course, when that was meant to be the emotion I felt – and thanks music go to Mark Knopfler for his soundtracks of Last Exit to Brooklyn and Local Hero and Cal, thanks to Danny Elfman and Wendy Carlos and Bill Conti and so many others (Thomas and Randy Newman, Hans Zimmer, John Barry, Howard Shore, James Horner and of course Bernard Herrmann ). It’s about individual films as much as it’s about particular composers – iconic title scenes and those moments where jump scares really thrill; cut to the cat jumping off a fence and knocking over the rubbish bin. It only works with the right music making it pop. The sound design and the director’s vision and the composer’s ideas all coming together. It surges and writhes, it gives pulse to the film, the music travels in waves, provides signs and warnings, it leads you down paths, it puts fear in your mind or hope in your heart. I can’t think of a great movie without thinking of the music that works within it. That sits all around it. Well, there’s Dog Day Afternoon – which has no score. But that’s a decision. The absence of score is the music itself, the poetry of that film dances unaccompanied but entirely on purpose. There are other examples of movies where the music is almost not there at all. And it is not because they hired a composer that didn’t do a good job. Or because they couldn’t find a better score. Rather, because the music was already there in the film. The music was written in the lines of dialogue, in the movement of the actors, their expression, their rage, the notes they gave – and then were given by producers, the writer, the director and co-stars. It’s a team effort – always. Still, I can’t help but notice the score. The good music will make me want to further engage with the movie. Bad films sometimes have terrific music. The wrong music sometimes frames a very fine film. And I’m there for all of it. The waves, the movement, the moments, the music, the profound poetry of movies and music and magic – the lights, the camera, the action all framed by the sound of someone’s inner vision.

The Age of Aquarius Will Outlast Us All

The Age of Aquarius has played all through my life. I’ve been aware of it forever. It was here long before me, it’ll be here long after. It seemed kitsch when I first noticed that I’d heard it. Shortly after, it felt perfect. It’s always seemed like a song that wasn’t written, that just evolved into being. Hilarious, given it was made for a show – the epitome of writing to order. A labour of love, quite possibly. But something laboured over, constructed. Built. But that version by the 5th Dimension really pops, doesn’t it? It reminds you of the power of a record. Some songs are immortal. Some records are the greatest. And if you’re really lucky you’ll get the winning combination: a record made of a song that kills. Such a version. Such a wonder. That is the magic of music. Kitsch and then suddenly – and forever – classic. I think about this song a lot these days. And most day I’m sure it’s one of the ones that will outlast us all.

Could Parasitic Fandom Ever Mean Anything: When Eminem Wrote Stan

When Eminem sang a song called Stan, he imagined a world where a crazy fan was outraged by the star not recognising how much he cared, too busy to reply uninterested in acknowledging that it was the fans that helped make stars who they were, how they are and what they became. It’s a lurid fantasy that is brilliantly realised, deftly written and delivered at the first peak of his fame. It rides along on another song, making stars of both Eminem and Dido. (I’m sure she wanted to thank him for giving her the best hit of her career). I was only an Eminem fan for a matter of minutes in the scheme of things. The cartoonery meant it could never stick for me. It was clever but not very musical – it was tactical but not very tactful, impactful but not really as radical as the hardcore might tell you. And besides he just yelled at you, words sticking sharp like they were caught in his throat and the violence and misogyny was mostly boring to me and my white privilege. There are moments. And Stan is one. It’s held up well – because the writing is there. It’s on full display. It’s still crushing to this day. Still real. You still feel every word that he spits, it sits heavy in my mind, it wears heavy on your heart, in your soul – there’s control in the way that he phrases, and places the words. And the choices are smart. And there’s art. There is art in the way he chooses what to say. That’s the thing with it. That’s why it’s one of his best. And some twenty years on – it’s like hearing a classic rock song. Which is wrong. On so many levels. And not what he planned when he wrote that song Stan. But also the kids of the people that probably wrote the song off as rude and silly and shouty and nasty have grown up to call themselves Stans when they’re obsessed as great fans of the untouchable and unreachable. They stalk Twitter and yell at thin air. They care on a level that just isn’t real. They feel outrage at the thought that someone could care less than them. But, as with the worst of any fan, their crime is that they’re not really listening at all. Which is the first line in the job description. The worst irony of all is to give yourself the name of the cautionary tale as a way of suggesting you’re above and beyond. But these are irony-free days. So the Stans have their say. And play it their way. And we’re all just a meme away from being cancelled. Eminem is worth millions. And some people think that’s the real crime here. When he wrote Stan he did more to help the world than most of us could ever know or will ever do. I listened to it for the first time in an age just the other day, I didn’t hear much of his rage, just compassion and craft and care. Imagine the drafts, and the world that went into that. Imagine the read-backs and the rough notes and the decisions. Imagine reading tweets where people call themselves Stans. Imagine still thinking “rap is crap” and feeling okay about saying that. Like it was an opinion that mattered or meant anything at all. Like parasitic fandom could ever mean anything.

Brian Wilson In His Room, Making Art

Brian Wilson is in his sandbox, making art. The grit between his toes calms the flitters in his heart, at least momentarily. Tearily, he’ll circle Gershwin, wash through Mozart, change lanes to get ahead of McCartney. Smartly, he goes wherever his mind takes him. Sadly, that’s far too many places. But we get round, round, get around, we get around and stamp our passport as we flyover and stop in on his various sounds. We are the lucky ones in his life. Those little symphonies, perfect slices of magic. We watch them and hear them – they appear then disappear before our eyes and ears. We cannot comprehend the full beauty and magic genius that pushed them into place. The sadness and baggage that allowed that to happen. Surf’s up, uh-huh. Corks on the ocean. The wind chimes of his mind. The great sadness that headlines far better as madness. Perfect melodies, wizardry behind the harmonies, and the deeply mournful soul-stirring heartbreak that triggered it all. Love. And Mercy. He ran in search of both, he wrote in search of either. His music lives to celebrate what he has barely been able to enjoy himself. In his room. That magic world.

*

Okay, that’s for more than enough for today. These have been fun to write, or, um re-write as it were. To reshape, reposition. I have a few more. And I have others in mind. So we’ll see where it goes, but love to know if you think these work at all?

And for your troubles, I have our regular playlist – it’s Volume 56 of A Little Something For The Weekend

All best to you and yours, have a great weekend.