In(side) A Galaxy Far, Far Away

Friday is about music, so there’s playlists and links. Today, a little look at the most amazing decade-long run of music by one of the greatest film composers of all time.

Last weekend I was dragged along to watch the first two Star Wars films on the big screen for May the 4th — ie: May The 4th Be With You. I was even dragged back the next night for Revenge of the Sith, the last of the mostly lacklustre prequels (ie: Revenge of the 5th). I like to think this is Good Dad behaviour. And in the case of the first night, it was a family outing, which meant poor Katy finally had to sit through not just one, but two Star Wars films (she’d held on, lifelong, to never seeing anything to do with a franchise most people can’t escape).

It was less than a year ago that I tried to watch the first Star Wars at home, for at least the umpeenth time, and really struggled. Declaring myself out. No longer a fan, if I ever truly was (and I think I was caught up in it massively as a kid, how could you not be, and who — apart from my wife — wasn’t?)

Anyway, as I sat in anticipation of the opening sequence, and the nearly five hours to follow of Double Feature, one thing saved me:

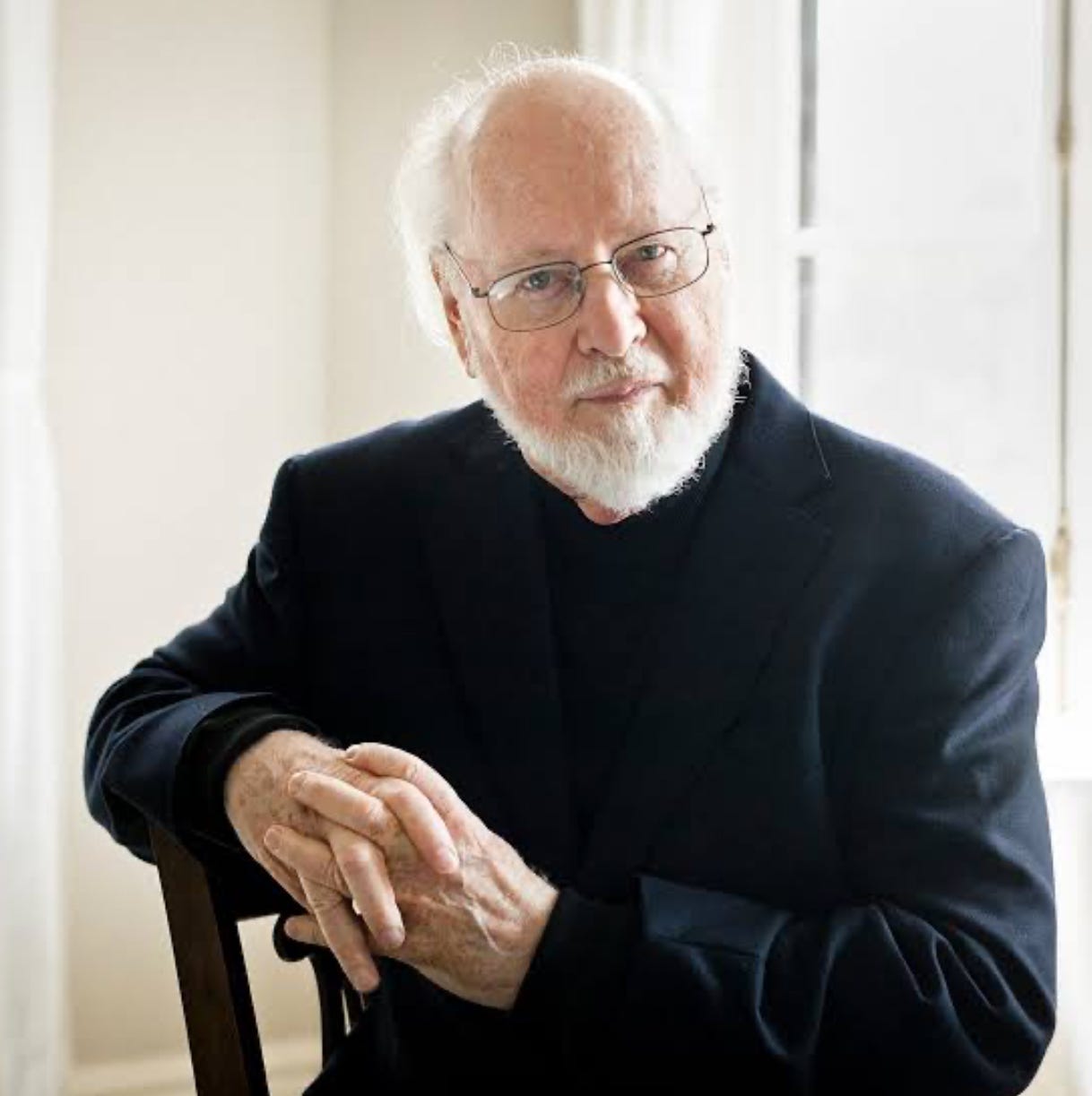

The music of John Williams.

It propels the film. All of the films. But it was so noticeable on this watch of A New Hope (and then Empire to follow) how Williams’ score all but holds the hand of the viewer to guide them through the scenes. Or it holds the hand of the scenes and helps thread them together. It really is amazing.

I’m a fan of Williams’ music — as a hopeful soundtrack buff, I feel he simply can’t be ignored. And why would you want to anyway? Sure, there’s some big, grandiose stuff - but usually because it needs to be there — but there’s a lot of subtlety in the man’s work too. Some incredible scores that offer genuine surprises.

I thought about writing something connected to John Williams to mark his 90th birthday. But how do you even start such a thing? And so I didn’t, and that was now two years ago. He’s not only still with us, but still creating, now conducting rather than composing — but still regularly releasing new works and touring the world on a perpetual victory lap, that is so earned:

Saito Kinen Orchestra / John Williams / Stéphane Denève: John Williams In Tokyo

It’s impossible to contextualise Williams’ contribution to film, beyond saying he is one of the absolute greats — up there with with Alfred Newman, Bernard Herrmann and Ennio Morricone, if there’s ever a Mount Rushmore of Film Composition. And really, second only to the great Maestro Ennio in terms of modern day impact. Though of course he’s far more of a household name — because he’s worked more in the mainstream, obviously.

When I was watching the three Star Wars entries over the weekend, I was pulled along by the music. By Revenge of the Sith we have all of the great individual character themes in place, so as we are catching up to the original trilogy’s timeline and seeing the virtual birth of Darth Vader and the literal birth of Luke and Leia we have their individual character themes wafting through the sequences to guide us. It’s beautiful hand-holding, and world-building, or world re-entering, even.

There’s also just so many iconic cues in those earlier films, from the wild Cantina bar scene to the icy world of Hoth, to Yoda’s swampland, and the rousing battle sequences.

My mind drifted during the films to what a run of work Williams made in conjunction with Steven Spielberg. Between them they created the modern day blockbuster. It’s truly a partnership, when you think of the music Williams made, iconic themes and sequences in all of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises, in E.T. And of course it really all started with Jaws.

How many famous film scores are there, really? I mean there are those of us that listen to them. But the ones that have permeated the culture, as single pieces of music, parodied, or used sincerely to signal loving tribute parodies, and still able to stand up so many years later with the original work, as well as being heard in a variety of contexts. John Williams is, for this alone, the gold standard, right?

So think about the run of music he made for films between 1975 and 1985. It’s one of the most mind-bogglingly brilliant bursts of constant creativity.

Williams was born to a musical family, and went on to Juilliard to study piano. He was going to be a concert pianist, but moved toward composition, particularly after being mentored by the likes of Herrmann and Newman, and recording piano parts on some of the most legendary films of the early 1960s. That’s Williams playing the piano on Peter Gunn (1959) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). He can be heard also on The Apartment (1960), Days of Wine and Roses and To Kill A Mockingbird (1962). Oh, and that’s him on a little film called West Side Story (1961).

He’s recorded chamber works, including his own compositions, in the late 1950s, and across the last 30 years he’s returned to this work, alongside creating towering film scores for Schindler’s List, the first three Harry Potter movies (including the iconic individual character themes, again), and, well, you know, a little film called Jurassic Park. And just so many others…

It’s dizzying to think about. It’s too much to take in. Hence me never really writing about him previously.

There were scores under his own name from the late 1960s and through the seventies, including back to back “disaster” films, Earthquake and The Towering Inferno (I love finding Williams scores on vinyl). But really, he still seemingly comes out of nowhere in 1975 when he works up a two-note obstinato that will make generations of children afraid of the water.

The podcast Blockbuster, released about five years ago, tells the story of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg all but unknowingly creating the world’s modern day blockbusters.

It’s a great series. And pays nice attention to how crucial Williams’ scores were for Jaws, Star Wars and Close Encounters, all created closely together in time.

So yeah, this got me to thinking about what he achieved in this decade. The fire fully lit.

One of my favourite things to think about with music is when an artist has a sustained run. Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell in the 70s. Elvis Costello from, say 1977 to 1987 (some people would cut him off at 1982, but not me). And Brian Eno from 1974-1984. There are other examples, but I’d never really thought about a film composer before in this way. Williams has a decades-long working relationship with Spielberg, best exemplifed in this early run, but he also worked with other directors in and around those films - creating legendary scores for Dracula and Superman, and many other movies besides.

Take a look and/or listen to the below. What a lineup:

These scores changed cinema. Changed cinema scoring. Created worlds. Changed lives. And they are just some of the scores he created in that one decade. And just a snippet of a snapshot of the work he has produced. So, as you plan your nice casual Friday, maybe dipping out a bit early, having a longer lunch than usual, pouring that first drink a bit larger and a bit quicker than on other days, think about this incredible run of music that helped to make movies that impacted the world.

But hey, I get that movie scores aren’t for everyone, so I’ve got you covered with vol. 168 of our weekly regular podcast.

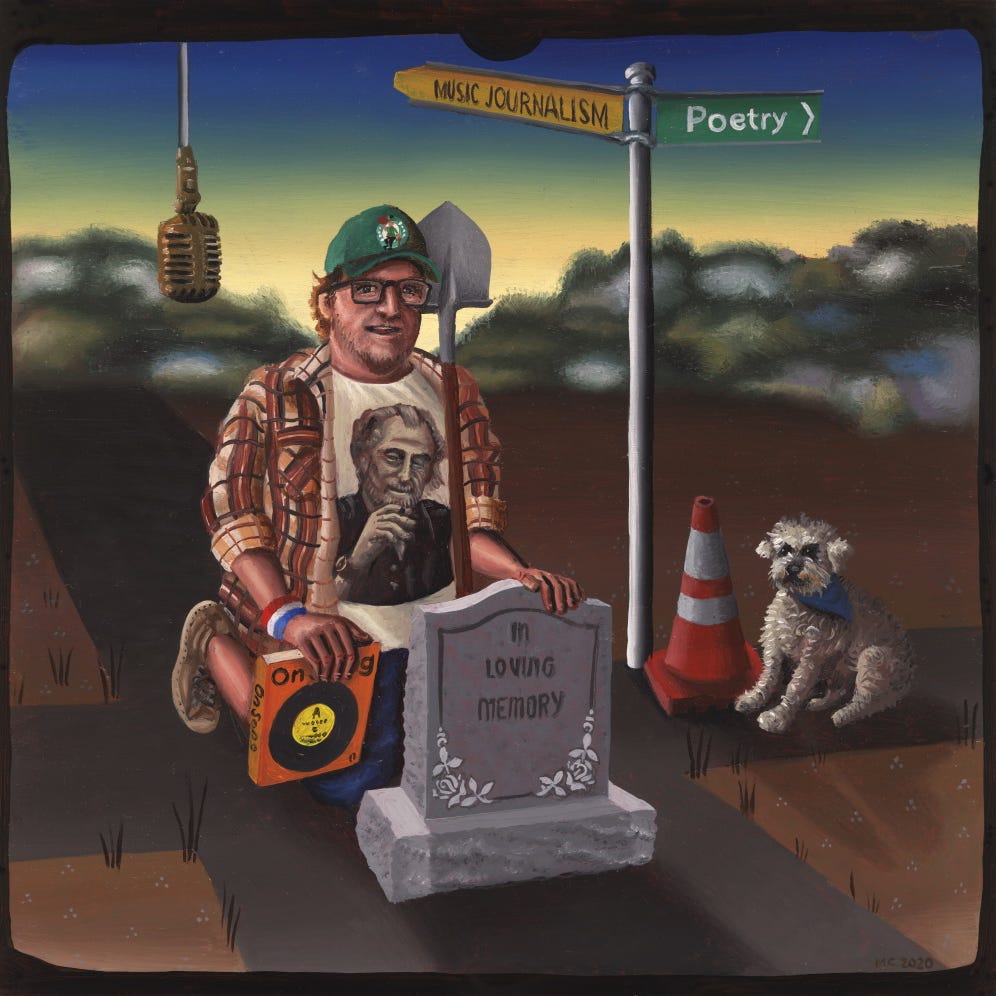

And you’ll see by the picture there, I dedicated this week’s volume to Steve Albini. Though it’s not exactly a very Albini-sounding playlist. Quite the opposite in fact. But if you missed it yesterday, I did pay tribute to Steve Albini. R.I.P.

Jeepers that is certainly knocking it out of the park.Being ignorant to soundtracks I never realised he did all of those....most composers I imagine could only dream of doing just one of them!