How The Culture of Modernism Made a Way for Hemingway to Become the Literary Role Model for a Type of Toxic Masculinity

Wednesday is about books, and writing. And reading. Here’s an academic essay I wrote recently about Hemingway’s role in the mainstream “modernist” birth of Toxic Masculinity

“Got tight last night on absinthe and did knife tricks” — Ernest Hemingway

[in a letter to a friend][i]

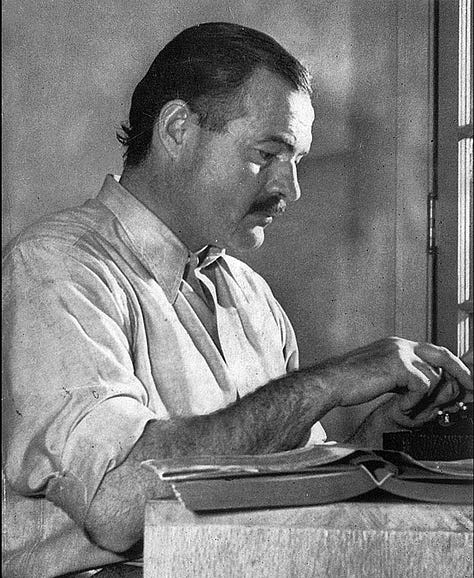

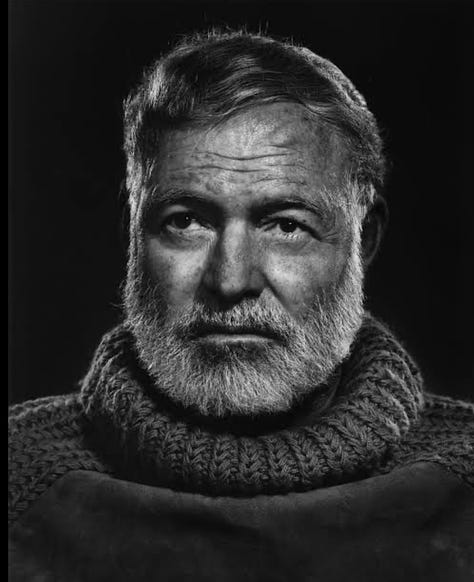

It was not Modernism that made Ernest Hemingway a pin-up for toxic masculinity — Modernism gave him the license. From experimental structure and open endings to a focus on his post-war pursuits, the tough man of hunting and fishing, the lone man with a drink at the end of a day’s demanding work, be that writing, or fighting, or both, Hemingway can be seen an an archetype. It was not Modernism that made Hemingway the literary role model for a type of toxic masculinity — but then again it was. He wrote his version of Walt Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’ through almost everything he published; the Hemingway on the page was the reinforcement of masculine ideals such as strength and dominance, and from there to a hyper-masculine model that normalised the stoicism and suppression of emotions, and a reliance on alcohol and justification of it as “the Giant Killer” and a type of “food”[ii].

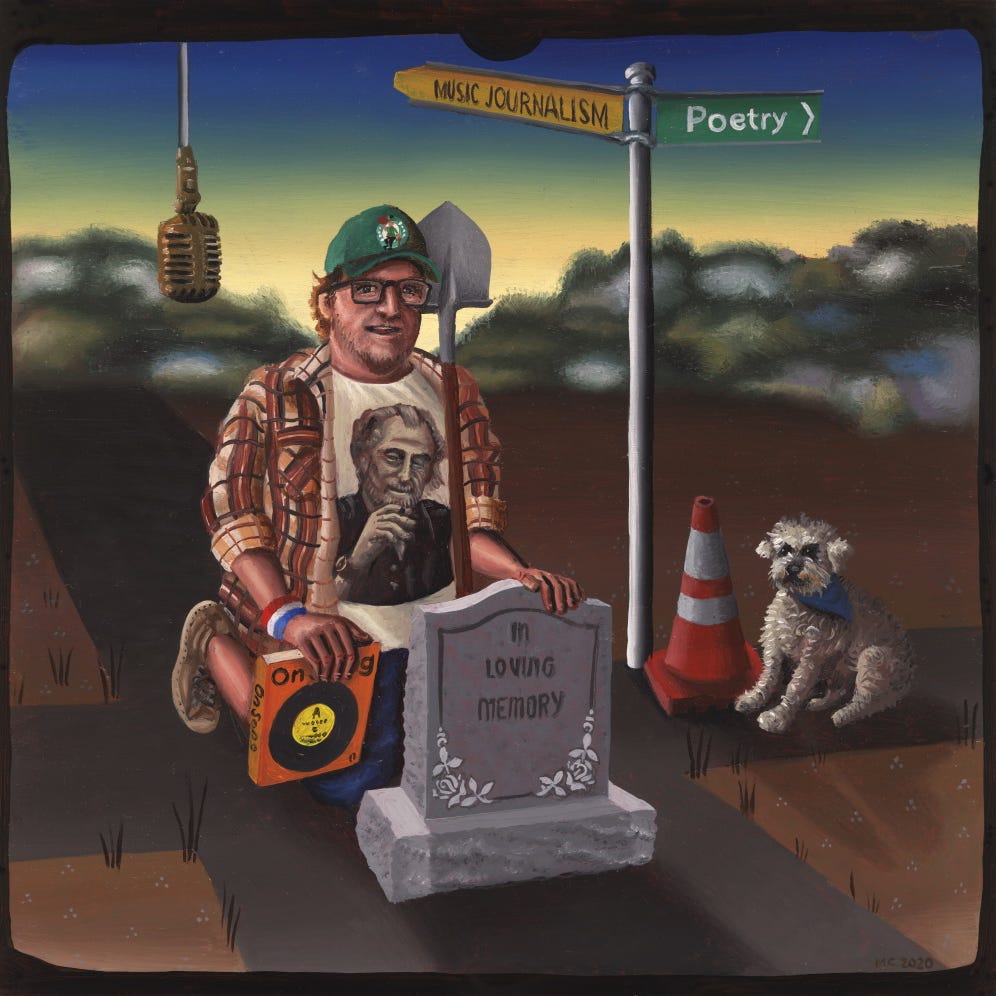

The problematic tropes of masculinity were well explored by Shakespeare in his tragedies (Othello and Richard III would provide two of the most obvious examples) and through Milton (Satan, Paradise Lost), as well as many of Modernism’s male writers (Pound, Fitzgerald, Lawrence, Joyce, Faulkner), but the way Hemingway himself embodies the very definition of this stoic male, and his profound influence — helping to create other male writers that focussed on (their own) masculinity — is an important part of his legacy. He all but redefines the way masculinity is presented and then written about by the next wave of writers, in particular Norman Mailer (machismo), Charles Bukowski (alcohol fuelling cynicism and then rage), John Cheever (inner turmoil) and Raymond Carver (emotional isolation), many of them also finding much to admire and mimic with Hemingway’s pared back style.

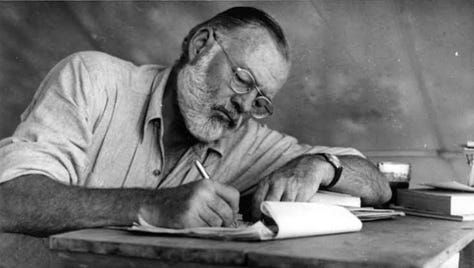

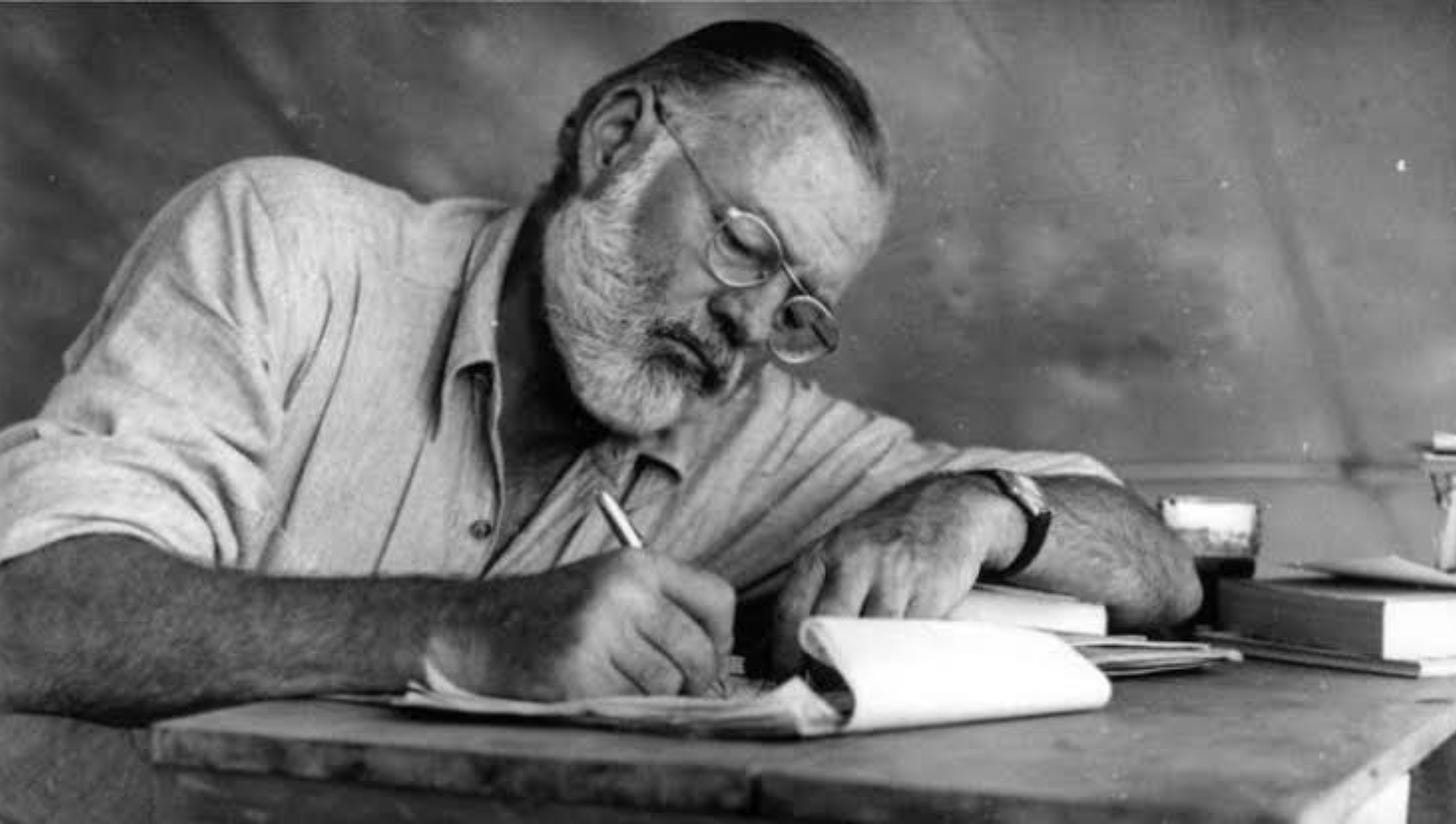

Modernism’s clean break from the flowery prose of the romantic novels that were so often tied up neatly at the end with a bow, meant a pared back writing style would allow for deeper, darker truths to be pushed onto the page. In turn, the simple and direct sentences, the focus on dialogue, the space around what is not said being at least as important as what is being said, all played to Hemingway’s strengths. His journalistic training had given him the stone to sharpen his blade against. It is obviously unfair to simply describe the male characters he created as toxic or troubling for their hyper-masculinity, the interiority of Hemingway’s characters allowed for trauma or other emotional pain which, in line with Modernism’s interest in the great unsaid, and the fragmented nature of indentity, allowed for brooding, intense characters. And if Modernism wanted psychological depth as an alternative to the elaborate ‘storytelling’ of the late 19th Century, and before, then Hemingway would help to break that mould with male protagonists that held their emotional complexity deep within, that spoke, or were spoken for using terse lines, understated, stopping short, both on purpose and with purpose. He was drawing from his real life. He was hoping to show characters with a tough exterior, but hairline cracks revealed a person broken on the inside, searching for meaning in a world that did not care about them.

Hemingway’s own experiences in the first World War (ambulance driver) left him scarred, both physically and emotionally and that trauma, that emotional withdrawal, is all through his work. Modernism seemed to arrive at exactly the right time to give him the lens to explore this, without really exploring it; to dump it rather than unpack it. This is where critics have pointed to his characters not using memories and sitting in the experience of a moment rather than drawing from a memory.[iii] In the relatively recent biography, The Man Who Wasn’t There — A Life of Ernest Hemingway, Richard Bradford believes that the “startlingly original” novel, The Sun Also Rises, is “driven by something far more personal and vindictive” than being his contribution that adheres to the modernist ethos; his effort after connecting with Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and seeking to sit on their level.[iv] Bradford believes Hemingway was “getting rid of his recent past” and says the pared back manner of the prose was less a contribution to the era and more likely “the most efficient way in which to extinguish and humiliate his erstwhile friends. He did not properly comprehend let alone care about the artist ambitions of his Parisian companions, and in the novel he dispatched them to oblivion”.[v]

Hemingway’s ability to show his character Jake Barnes (a thinly disguised version of himself) as battling an existential crisis, flawed and vulnerable, suggests the nuance that registers the book a modern classic. But the post-modern critique of it by Bradford suggests a more cynical intention, and speaks to the point of how his influence on Mailer, Bukowski, Cheever, and Carver is profoundly toxic — from the creation of the alter-ego via character pen-name (usually Nick Adams, just as usually in Bukowski it’s Henry Chinaski, or ‘Hank’ stepping in for Chuck) down to drinking as a crutch, and the wallowing in emotional isolation to the point of becoming downright un-relatable, or at least unreliable, maybe even unwilling.

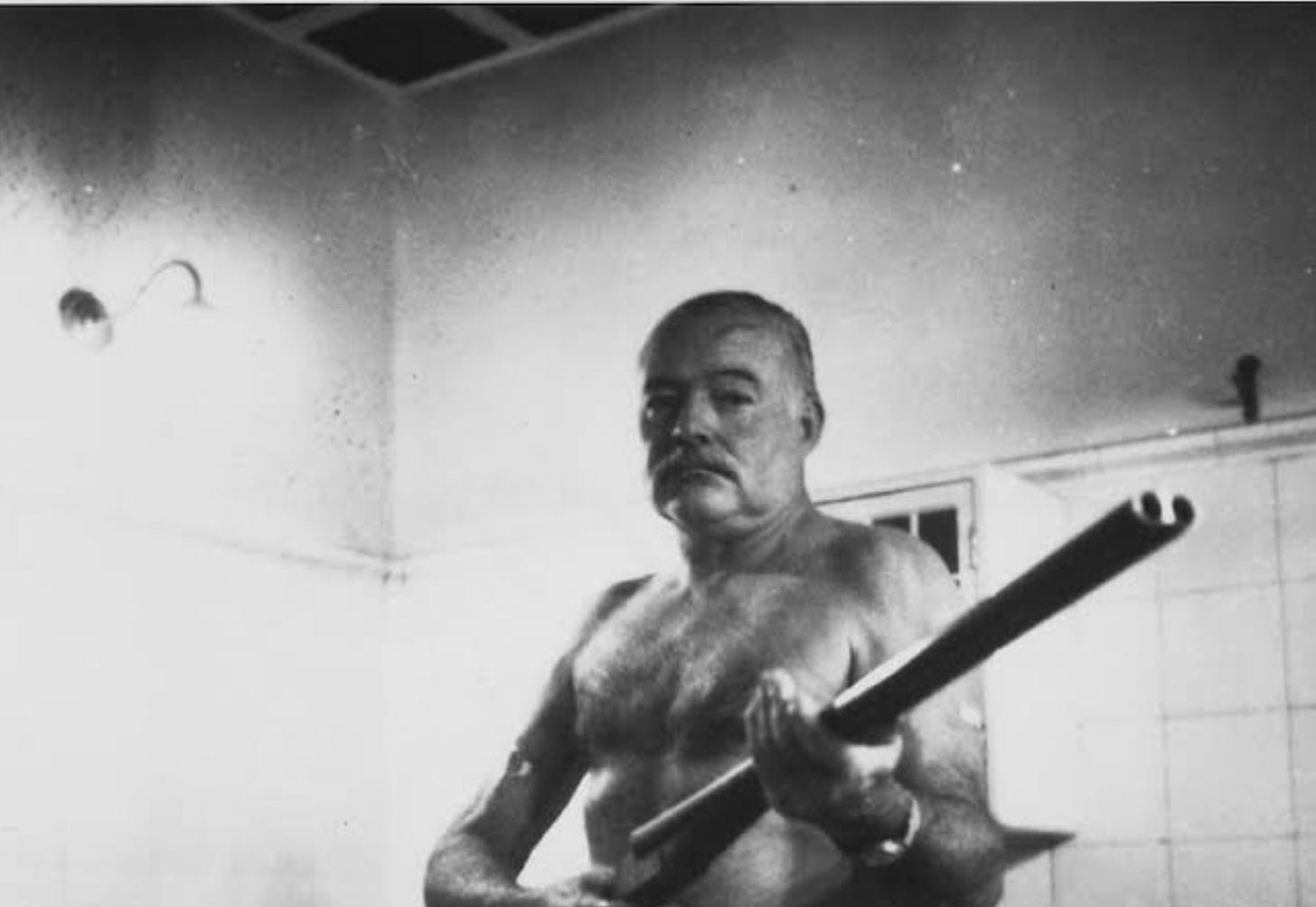

Judith Butler’s belief that “gender reality is created through sustained social performances”[vi] goes some way toward understanding Hemingway’s need to position his men with a capital M, shirts off, sweat dripping, rifle handy. The bullfights, the man alone with his challenge in the water both physical and emotional, existential in fact, The Man in the story ‘Hills Like White Elephants’, vs merely The Girl. It might be fine to read the story and decide that it is simply a way of not naming names, but there is an inherent power imbalance. Because we are never given the context, and must guess at it, we could assume that he is older, she is younger, and so ‘man’ and ‘girl’ are being used to explore that, but when looking at the canon, the “sustained social performances” that Butler is concerned with, start to topple over from power imbalance to inappropriateness. Bradford calls the 1950 novel, Across The River and Into The Trees “the nadir of his career as a writer” [vii]; going further to call out its “macho fantasy with a hint of paedophilia”.[viii] And if that’s going too far, and entirely a product of a post-modern view looking back at Modernism, it also picks up on Hemingway’s simplistic treatment of his female characters. If this did not topple all the way over into misogyny, it certainly did in the work of the male writers that took their cues from him. In particular, Mailer and Bukowski took the emotionally stunted male characters and pushed the self-destruction in the direction of outward aggression, actual violence, and most certainly misogyny. Though Hemingway aimed for psychological depth via the minimalism of his writing, he also settled for action over introspection. Modernism was interested in the unsaid, but Hemingway too often allowed for the unexplained. He might have been absent from judgment across the pages, his narrator absent throughout so many of the short stories, the reader left to decipher pages of dialogue and sometimes getting lost around who is speaking — but he was reinforcing who he was and how he acted through those various stories; the writer embodying the role and establishing a cult of personality. Again, in Charles Bukowski’s story, ‘Class’, he gets into the boxing ring to take on Hemingway. They fight each other with their words, literally throwing pages at each other. Of course it’s Bukowski’s story, so he emerges the victor. [ix] Bukowski was competitive, and often threw shade at writers in his poems and stories, but Hemingway was a special focus — which speaks entirely to both his influence and status. Even with ‘Class’ being read as tongue in cheek, it is still ambitious and aspirational of Bukowski to imagine himself the winner.

The Author’s Proxy most commonly used by Hemingway was Nick Adams. All through his early stories, Adams is someone who retreats into nature (‘Big Two-Hearted River’) relying on something close to animal instinct to survive the (self-inflicted) alienation of/from the modern world. Modernism’s break from linear narratives and fixed character identities, allowed Hemingway to explore his own masculinity via Nick Adams. The tough exterior is a hard shell for a fragmented inner self. It is unfair to level at Hemingway an inherent toxicity in this — but his influence has promulgated that negative ideal. Masculinity was in crisis following World War I, Hemingway is often criticising that silently, by displaying men lost in the woods, or at home in the actual woods because they’re lost so deeply in that metaphor; lost in or to themselves. One reading of Nick Adams is to see him as a prototype for Sylvester Stallone’s John Rambo. Not the Rambo of the action sequel blockbuster movies, but the returning army soldier of the first film from 1982, based on the David Morrell novel from a decade earlier, First Blood. And when Hemingway subs Adams for Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises, he strikes him down with impotence, a literal representation of the old model of a hero no longer being effective.

But again, I point to how this was read by the writers that followed. For maybe they are to blame for the post-modern critiques of Hemingway. Cheever’s Neddy Merrill in his most famous story, ‘The Swimmer’, is about as fine of an example of personal insecurity wrapped in the riddle of suburban malaise. Neddy’s surreal journey, swimming home via his neighbours’ pools, is a metaphor for the unraveling of his life. He is the embodiment of Cheever being frustrated with the trap of modern life. And Raymond Carver’s Author’s Proxy for his most famous story, ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Love’, is named Mel McGinnis. But McGinnis is there as stand-in for Caver’s battle with the bottle, and with women. McGinnis is full of bravado and vulnerability, in a leaf out of Hemingway. But there’s a darker side hinted at, with the alcoholism being the seed of emotional frustration and troubles. Where Hemingway might have framed his drinking, and his characters’ drinking, as something quite celebratory, for Carver it was secretive, it was shame. Could these examples, so clearly taken from Hemingway, be doing the damage. Or was the damage always there, when we think of how secondary the female characters are, existing, as in ‘Hills Like White Elephants’, largely as something for the male character to project on to and bounce off from; the women seem one-dimensional in comparison to the men. Did this open the door for Mailer and Bukowski’s misogyny; for Carver and Cheever’s aloofness, depression, and emotional abuse?

Masculinity had been written without a shining light before Hemingway, but his characters that fought, took risks, were excessive in their drinking, deeply repressive of their feelings, might well have been searching for the meaning of their own life, if not life in general — but they became archetypes for a particular beast. And where are the female writers that have taken this on in the same way? It’s been said that Joan Didion’s restrained prose (and journalistic background) could echo elements of Hemingway, people point to Flannery O’Connor (precise language, dark themes), and Lorrie Moore (minimalism). Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro might have come closest to creating the ‘female version’ of Hemingway, and both had been open about respect for his craft, but really there was no direct comparison in the way that there was a line of conscious imitators on the male side. Modernism’s minimalism might have meant that women were written (off) as symbols rather than well-rounded characters, but it they are only there to service as a foil then there is an imbalance. In the hands of male writers all but owning up to their own insecurities, female characters suffered. The dominance of male characters, from male writers is something that could be dropped at the feet of Hemingway as if the head of a hunted trophy. By positioning the female character as something the male character had to conquer, or ignore — simply one or the other — he made it entirely about male identity, male struggle, the male story.

Do we blame the alcohol as the through line? It is there in every author that picked up Hemingway’s influence and dragged it like a hungover body through their own work. Hemingway “thought that he could quit drinking at any time, but knew he didn’t want to”, according to a letter he wrote to Archibald MacLeish in 1943.[x]

Even Stephen King, a writer more often accused of maximalism than anything resembling minimalism, invoked what he called “the Hemingway Defense” with regard to his own drinking.[xi] Writing in his 2000 memoir, On Writing, King believed the Hemingway Defense to be: “As a writer, I am a very sensitive fellow, but I am also a man, and real men don’t give in to their sensitivities. Only sissy-men do that. Therefore I drink. How else can I face the existential horror of it all and continue to work? Besides, come on, I can handle it. A real man always can”. [xii]

Hemingway’s literary legacy must include the immediate followers he directly inspired.

A postmodern reading of his work invites critique of the way he wrote men. There is a context, and it was of its time, representative of a different era, with different societal pressures that the writing was influenced by and reacting to. But Modernism is what allowed Hemingway to become the archetype for toxic masculinity. Anything celebrated in its time will be questioned in the future. In the case of Hemingway, we must now wrestle with the way his direct writing influence, the combination of his content and themes, only resulted in further misogyny, deeper confusion, and repression of the male id, and so many pale, (stale), and of course male imitators.

[i] Schaffer, Andrew: Literary Rogues — A Scandalous History of Wayward Authors, Harper Perennial, 2013; P. 132

[ii] Laing, Olivia: The Trip To Echo Spring — Why Writers Drink, Cannongate, 2013; P. 86 (Both quotes taken directly from a letter Hemingway wrote to an F. Scott Fitzgerald biographer, but framed her in the way Laing used them)

[iii] Robinson, Kathleen K: "Testimony of Trauma: Ernest Hemingway’s Narrative Progression in Across the

River and into the Trees" (2010). USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

[iv] Bradford, Richard: The Man Who Wasn’t There — A Life of Ernest Hemingway, I.B Taurus & Co, 2019; P. 5

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Butler, Judith: Performative Acts and Gender Constitution — An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist

Theory, John Hopkins University Press/Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Dec., 1988), pp. 519-531

[vii] Bradford; P. 6

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Bukowski, Charles: South of No North, Black Sparrow Press, 1973

[x] Donaldson, Scott: Hemingway VS. Fitzgerald — The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship, John Murray, 2019; P. 244

[xi] Schaffer; P. 138

[xii] Ibid (Schaffer quoting from King’s book, On Writing)

SOURCES:

Richard Bradford, The Man Who Wasn’t There — A Life of Ernest Hemingway, I. B. Taurus & Co, 2019

Scott Donaldson, Hemingway VS. Fitzgerald — The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship, John Murray, 2019

Ernest Hemingway, The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, Scribner, 1987

Olivia Laing, The Trip to Echo Spring — Why Writers Drink, Cannongate, 2013

Andrew Shaffer, Literary Rogues — A Scandalous History of Wayward Authors, Harper Perennial, 2013

Jack London and Joseph Conrad before Hemingway, fleshed out themes of masculine, white superiority but he did it in Spades

'the unraveling of his life...'

What life ever starts neatly knitted together? Most people live trying to do just that, give the baggy woolly monster some shape.

A lot of thoughts in this paper that don't quite knit together either: 'toxic masculinity' is a bit of a Procrustean bed, it seems.

Would like to see more original and braver speculations on toxic femininity and the toxic, stupid, anything-goes liberalism that, for example, applauds females getting into a boxing ring with men, perhaps as drunk as Hemingway and Mailer, and losing their chivalry fast; but, given the biological realities, packing a much bigger punch.

'Toxic' can mean anything the cold-hearted observer doesn't want to deal with.

You want another biological reality? Most women want a man who can look after them. Most drunks can't look after themselves, which makes them unpalatable potential providers. Hence, possibly, the derision.