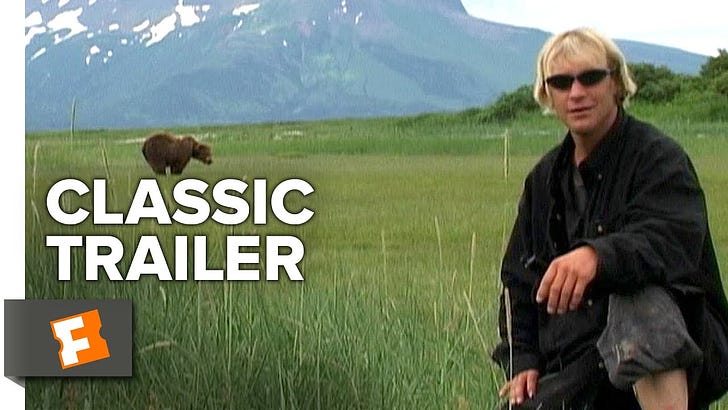

Grizzly Man: One of My Favourite Documentaries

Monday is Movies. Today's one is a retro-review...a classic doco...

Timothy Treadwell is one of the great flawed characters of cinema. But he is (or rather was) – and this is the best part – real; he was no creation – Treadwell was a real human and he filmed himself on a strange quest to become something other than a real human – extra-real, unreal, surreal – whatever his ambition might have been we may never truly know. But from the hours of footage that survive, Werner Herzog has fashioned a superb, funny, grim, sensational(ist), sublime, bizarre and always compelling documentary work. Treadwell himself may have been stranger than fiction could ever concoct – and there are moments during Grizzly Man that will have you pondering how far po-faced documentary can prod before revealing itself as more than the actual authentic antecedent of mockumentary and in fact its own mad strain – but Treadwell is the stuff of documentary gold. And Herzog proves himself to be the alchemist.

The unfortunately named Treadwell met his end in 2003, mauled and devoured by a bear in Alaska, having trodden one too many times down the bear’s path and around its home. Timothy was a filmmaker, a bear-sympathiser, a documentarian and self-styled, self-appointed expert on bears; indeed he believed himself to be not only a friend of the bears – but he was convinced the many Grizzlies he crossed paths with were in fact his family. His new family.

Treadwell’s expeditions began in 1990 and saw him appear on Letterman and speak to school class groups. He would spend his summer – alone – in an Eden he had created for himself, mingling with bears. Observing them through the lens, documenting them and narrating his own attempts to interact with bears and foxes. He named them (Ghost and Spirit are two of the foxes we meet, whereas the bears’ names run the gamut from human, Tabitha, to the more absurd, if not accurate, Mr Chocolate and Sergeant Brown) and he loved them. He really, really loved them. At least that’s what he tells the camera. Often.

Herzog allows Treadwell’s footage to tell most of the story – using some new interviews and discoveries to tie it all together. He begins by sympathising with Treadwell, sensing the spirit of a filmmaker that was clearly a part of this mad man on this (increasingly) mad journey. There are moments, as Herzog both tells and shows us, where Treadwell’s gung-ho/guerrilla shooting style allowed him to capture pure cinema magic. Foxes toy with the camera and run off with Treadwell’s hat. Bears gracefully gallop in search of salmon and fight for pride. But as the footage unfolds we see that Treadwell too is unfolding, slipping, losing his tenuous grip on reality. Grizzly Man becomes not just the tragic/funny story of a man mauled by the bears he loved which, let’s face it, served him right for prodding and poking in to another animal’s business. The film is far more than a survey of this landscape. It is a search for Treadwell’s identity – it is an expose on the man’s intriguing neuroses; his issues piled, well, bear-high at least.

One moment we’re musing at a fox playfully tussling with Treadwell’s cap, the next minute all façade has vanished as Treadwell abandons logic and takes chase, screaming at the fox, as if disciplining a very naughty child. It becomes hilarious, frightening and disturbing.

He is then shown doing multiple takes, essentially getting in character, working out what angle to take for his own footage. We also see him using the camera as a diary – confessing to his struggles with human relationships (when literally no-one asked). It does not take long to wonder as to why Treadwell is there and how he arrived at that point – both geographically and mentally.

Herzog speaks with his parents who dismiss early drug-use and alcoholic bouts, friends and ex-girlfriends seem to be caught up in the alleged spirituality of Treadwell’s quest, deciphering it as naturalist and wise. At worst it is hippie ideals making a comeback. But this is the jaundiced view of those close to Treadwell – and a separate argument might be to ponder who, Sergeant Brown and Mr Chocolate aside, ever (truly) got close to him. He was responsible for his girlfriend’s death too. Amie Huguenard accompanied him on his last few trips to Grizzly land where she met her grizzly death. She hated bears. We hardly get to see her on film, but Treadwell’s diaries, we are told, account Huguenard’s fear. Was she kept up there beyond her will? Was Treadwell attempting, however insignificantly, to create his own cult? These are questions that will stay with you after Grizzly Man. I was left comparing Treadwell to Michael Jackson – for his starched world-view, his faux-sincere “I love you” announcements tossed out seemingly at random as if justification for his most bizarre self-formed rituals and for his incessant idealism that there was nothing wrong with what he was doing, only right.

It’s almost voyeuristic watching Treadwell’s mental imbalance showing itself – but as with Capturing The Friedmans and The Devil & Daniel Johnston it becomes all the more compelling to watch. The motley cast of outsiders occasionally called on for extraneous comment recall the white-trash coterie in Nick Broomfield’s Kurt & Courtenay.

Richard Thompson’s lovely score – electric guitar trills and journeyman acoustic folk – helps Herzog to frame evocative scenes. The editing is a work of magic – that Herzog was able to make sense of this near load of nonsense is worthy of praise; that he was further able to make a case for Treadwell as a compassionate man clearly lost – then stack evidence to show his inner demons – and managing to remain objective as a narrator makes Grizzly Man a must-see documentary experience.

I’ve watched this film so many times, I’ve lost count actually. I first saw it at the cinema, and part of wanting to see it was simply because I’m such a Richard Thompson fan that I wanted to hear his music in the context of the film. There are parts of his score that remind me of Paul Kelly’s Lantana soundtrack, the waft and drift, the improvised parts falling into place. Part of me wanted to see it simply because I’m a Herzog fan – and yes, sure, he’s made better films but the part of me that returns to the film isn’t anything to do with Herzog or Thompson’s work, though I admire plenty about their efforts every time I watch it. The part of me that wants to watch this film over and again, seeing new strains of madness each time, is the part that knows what it’s like to be a dumb dreamer.

I don’t pity Treadwell, I don’t envy him. I’m convinced now he was living with some strange, dark secrets. Was he fighting substance abuse? Was he battling with his sexuality? Was he simply trying to find his own place in the world? Had he – in fact – done exactly that? There’s a lot of haunting, strange beauty in this film. That the serenity we see is served up only after we know about Timothy Treadwell’s demise, the grim ending of the story arriving in our minds before we see the tale play out, is one of many strange and wonderful aspects to this.

It’s a film that I’ve watched more than any other documentary – well, pretty much. The other docos I’ve named above are all ones I’ve watched several times. But I get the strange sensation, every time, to laugh at Treadwell and his story. Laugh, because if I didn’t – I’d cry. And I’ve done that too, watching this film. It’s a beautiful story. Shows we’re all fucking bonkers really – you can’t tell me that Herzog is any saner than Treadwell. No chance.