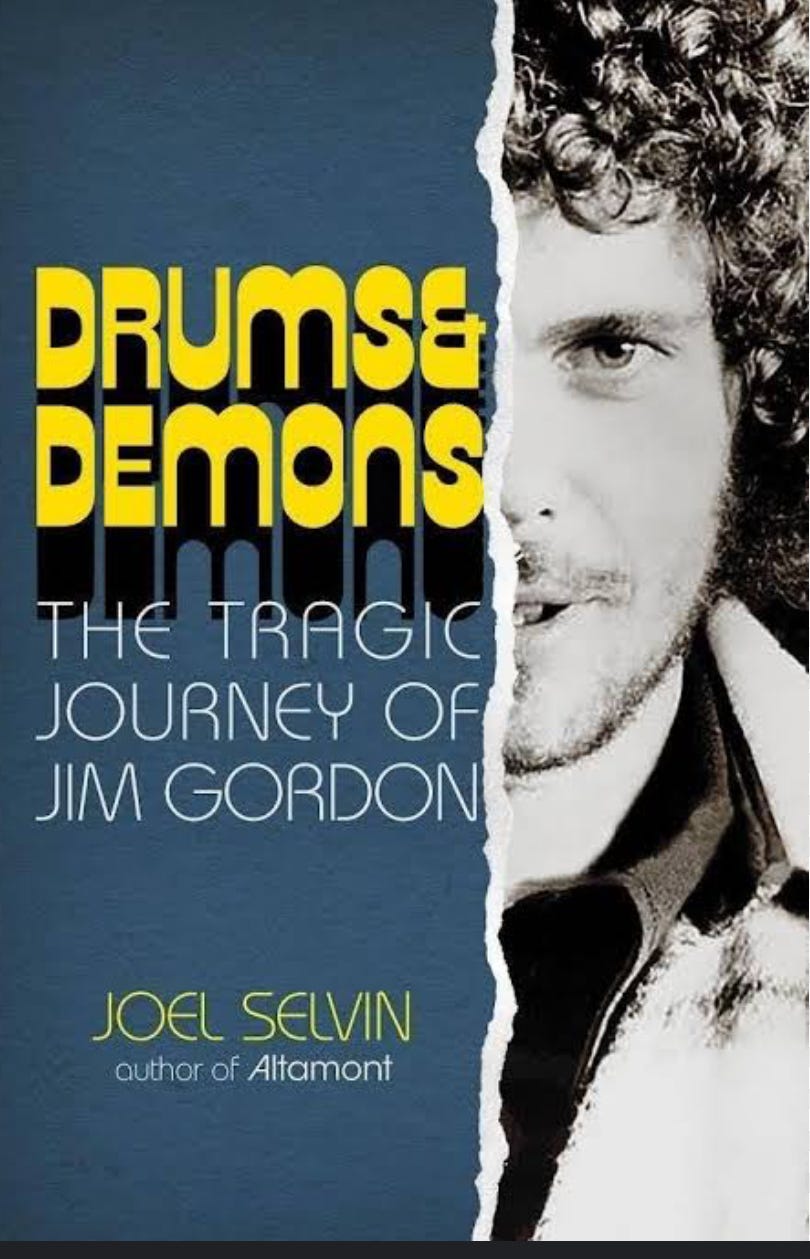

Drums & Demons Is The Best Book I’ve Read About Something Utterly Tragic

Wednesday is about books, and reading. And writing. Today, the biography of Jim Gordon. A tragic story, told compellingly, with compassion, with empathy. And yes, with love for the music.

I’ve just finished one of the best books I’ve read in absolutely ages.

And you know that feeling you have when that happens. You just want to talk about it — to anyone and everyone. You want to start conversations, find other fans, turn people onto it, hear from others who have experienced it already, and of course, on some level at least, you wish the book hadn’t ended.

Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon is by veteran music writer Joel Selvin (I’ve loved his writing on Altamont, and Stephen King and the other authors that formed novelty band The Rock-Bottom Remainders, and Selvin even managed to make Sammy Hagar’s life story readable ffs). It’s a non-fiction book, a biography of the drummer Jim Gordon. But if you don’t know his story already, the title helpfully tells you that it’s not fun.

One of my favourite drummers — ever — was Jim Gordon. I first knew about him because he played on the album Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs by Derek and The Dominos. That was Eric Clapton’s chance to hide for a bit, stepping back from the spotlight — though it didn’t really work out that way. Anyway, I was 8 or 9 years old when the needle first dropped on Layla, by way of the compilation album, The Cream of Eric Clapton. And it was mindblowing to me. The reason I found out the name Jim Gordon was due to him having the co-writing credit on Layla. He wrote the piano coda that extends the song beyond the riff’s natural reach. And when I found out that the drummer was responsible for that, it was my first indication that drummers could do more than just hit the lids at the back.

There’s actually controversy about Gordon’s writing credit — but I wouldn’t learn that for years. Apparently Jim stole the music (idea) from his then-girlfriend, Rita Coolidge. She was always missing out on the credit she deserved.

Anyway, this is not the worst thing Jim Gordon ever did.

But first, you need to know — if you didn’t already — Gordon was one of the greatest drummers ever. He was part of the Wrecking Crew. That group of studio musicians that played on every hit going for a while there. Gordon was a disciple of the great Hal Blaine. And in turn, he influenced the likes of Jim Keltner and Jeff Porcaro.

Anyway, you might not have needed to actually know that, but it could be useful to know that ahead of joining Clapton to make Layla, Gordon had already played drums on John Lennon’s Power To The People, and on Glen Campbell’s Wichita Lineman, and Mason Williams’ novelty/crossover hit, Classical Gas. Oh, and the Mel Torme sassy jazz stomper, Comin’ Home Baby, and, well, he’d worked with The Ronettes, The Everly Brothers, Bread, Crosby, Stills & Nash, and played on a song by The Stone Poneys (featuring a young Linda Ronstadt). You know that gem written by one of the Monkees, Different Drum.

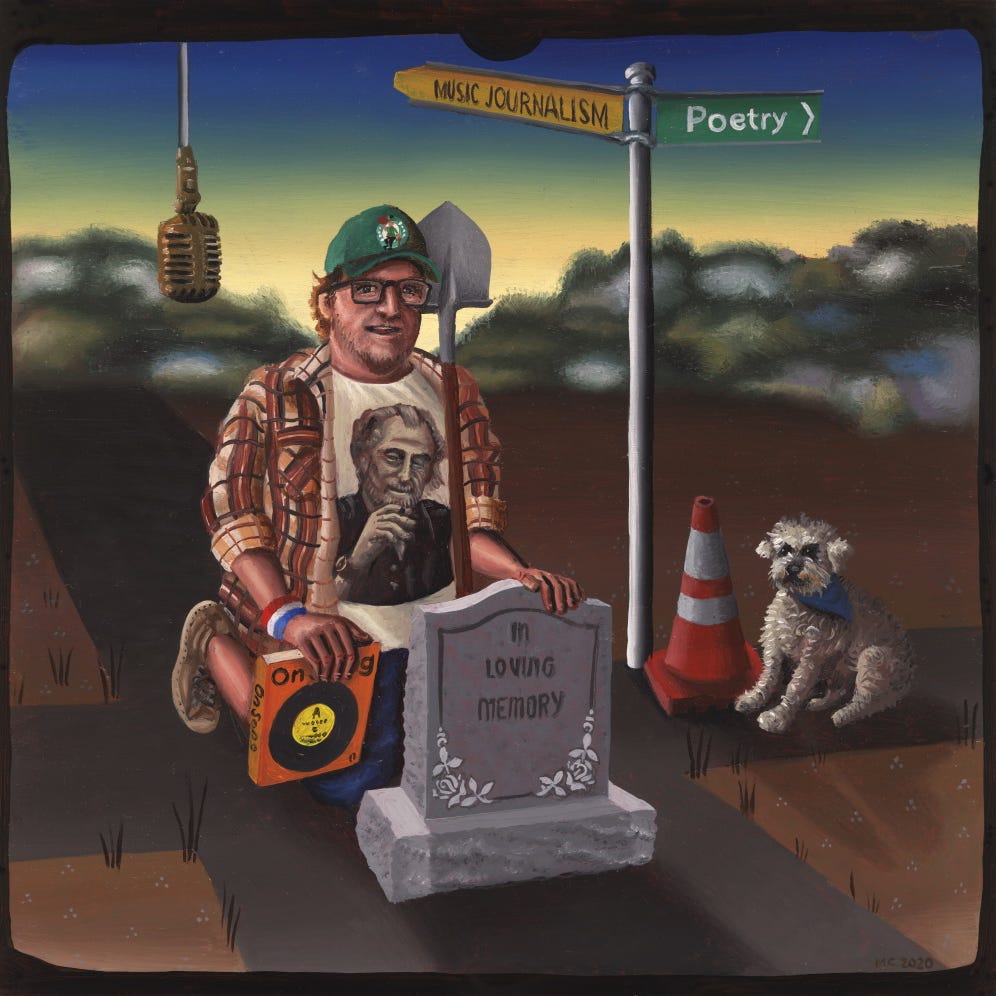

To help with all this BEYOND PROLIFIC context, I’ve made a bit of an exhaustive-sampler. I got carried away and made it 12 hours long. And it’s still barely skimming the surface. But seriously, he played on I Am Woman, and Diamonds and Rust, and My Sweet Lord, and Everybody’s Talkin and…and…

So that’s your forever-homework right there.

When I was a teenage Eric Clapton fan (I feel like that’s its own T-shirt), Jim Gordon was one of my absolute heroes. And then I heard about the story that seemingly stopped the world from ever talking about this legendary musician. At the late height of his fame, and still in the early 80s, Gordon still in his 30s, he committed matricide. He murdered his own mother.

The voices in his head told him to do it.

He took a hammer and hit his mother four times in the head. Then he took a knife and stabbed her in the throat. Jim’s mother was one of the voices in his head. He was a paranoid schizophrenic — it went undiagnosed for so long that by the time it came to diagnosis he was also a drug addict and alcoholic. Booze and drugs were his own weapons against the voices. And they nullified the medications he was meant to take, or made their side effects even worse.

It would get so bad that he’d have delusions he was on fire. Electric shocks would surge through his head if he could not silence the voices. One of the loudest was his mother — telling him off.

In the 1960s and 70s he was a prodigious drummer, a teen prodigy working with the Everly Brothers, playing on Phil Spector and Beach Boys songs. Then he was on albums by Randy Newman and Carole King and Carly Simon and Steely Dan. He was on tour with Eric Clapton and Mama Cass and Joe Cocker. He was everywhere.

Jim Gordon would fly to New York or L.A. to do sessions by day, and be back at Vegas for the night-time floor show. It was an impossible schedule he kept up for years.

He is all through everybody’s record collection, whether they know it or not. And on some of the most important records ever made.

He could play anything — usually first take. And he had the stamina to play You’re So Vain note-perfect for 60 run-throughs while everyone else sorted their shit out. Or to record a wild and loose drum solo in the middle of Harry Nilsson’s Jump In The Fire. You know…

But by the early 1980s, still across all the Hall & Oates hits and working with some of the same musicians he’d helped for years, still holding it together but falling apart, the reports started to change around his behaviour. He’d be sitting on a plane just stabbing the seat in front with a pocketknife. He’d be convinced it really was his mother telling him he was getting fat, or it was one of the other voices, one of his own — but also one that was never really his. And his brain was infected by so many devils.

The world stopped talking about Jim Gordon as soon as he went into custody for the murder of his mother. And I’m not saying he shouldn’t have been locked up. Or that it was necessarily correct to feel the need to trumpet his amazing playing, but for the last 40 years of his life he sat rotting (long beyond his sentence of a dozen or so years) — because it was too late. A system had failed him. A system wasn’t correctly in place. It was whatever it was, but it was the loss of a life, and it was end of another life really. And the end of a brilliant career.

No one has been able to correctly encapsulate this, until Selvin’s book — released late last year. A publisher finally agreed to take it on, after Gordon, aged 77, died whilst still incarcerated.

I’ve long been fascinated by this story — and Drums & Demons answered the many questions I had. It told me about a lot of music that Gordon was on, songs I knew and loved, but hadn’t known they’d benefited by his magic touch.

But can you still call it that, when those same hands…

It’s a tricky story to tell. And Selvin does it with empathy. It’s a thrill-ride in the early years, and someone else could make another 12-hour playlist and even that still wouldn’t capture all of the highlights (partly because it’s hard to know, on some of the sessions, whether Gordon was just shaking a tambourine at times, or whether he was covering fully for Blaine in his absence). It’s crazy to try to understand just how much work he did.

It’s also tricky when you start using words like crazy…

Selvin gives you so much with this book — but never basks in the sadness, or madness. He is there to point out all of his Gordon’s strengths and flaws, to build a portrait of the human being. Because anyone has ever known has been the name as a credit on record sleeves, and then as a headline for committing one of the biggest taboos. In the 20 years that Gordon was working, and having a hand in changing the lives of so many with his contributions to so many amazing songs, he was slowly losing his grasp on reality. It wasn’t his fault. He wasn’t treated accordingly. And when he was, it was too late.

There’s some harrowing moments in the book, but they’re never paraded around as any sort of torture-porn.

This is quite beautifully written — particularly its bookending chapters that deal with Gordon’s incarceration.

This was a book I’d been waiting so many years for. Long before it was ever written. And when I finally got to it, I devoured it in almost a single session.

So sad. So grim. Some tiny moments of inspiration in there — and some enduring music. Good people do bad things. Bad people are capable of good. Human beings are complex. The mind is fragile.

When I was 8 or 9 and first listening to Layla, when I was a teenager first obsessed with the solo albums of The Beatles, and when I was in my 20s and gobsmacked by the early Randy Newman albums, it was all long after Jim Gordon had committed his crime.

I can’t remember exactly when or how I found out, but it happened quickly enough, as it does when you get obsessed with music, and read as much as you can find on a subject.

It never felt right to talk about what an amazing drummer Gordon was, but it was obvious whenever you heard his perfect playing. And then, last year, he died. And people seemed to think that 40 years was long enough. There were a few tributes. But of course they had to mention what happened outside of the music. It hangs there. Heavy. Forever. It always will. And there will never be the correct answer. Only more questions.

Oh my days...I have to read this. Knew about the crime but are gobsmacked by so many of the juggernaut tracks he played on....sad that he was incarcerated for so long in a country that has little interest in rehabilitating it's sick and broken.

Thanks to alerting me to this book Simon and that Jim Gordon is no longer with us - how did I miss that!? I’ll blame it on Covid. Being a Steely Dan fan means that’s where his work means the most to me so I look forward to delving into your playlist and appreciating just how much wonderful music he’s played a major role in.