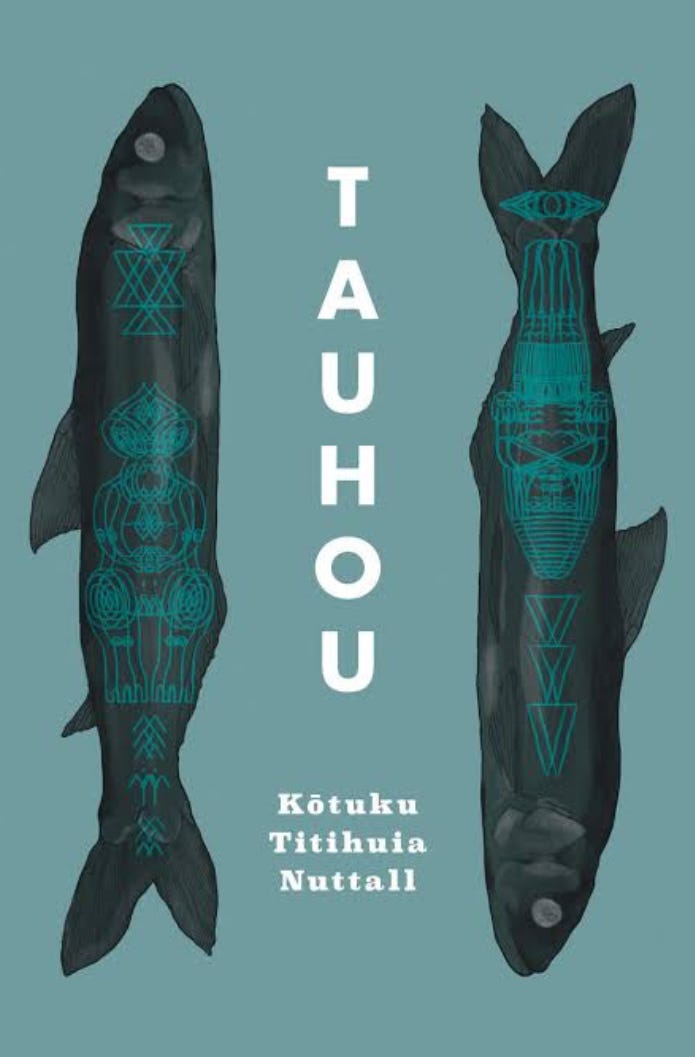

Close Reading: ‘Blankets’ from TAUHOU by Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall

This is an attempt to unpack the prose piece ‘Blankets’ from TAUHOU by Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall, Te Herenga Waka Press, 2022. The passage is taken from Page 47 of the text.

Technically this is a ‘chapter’ in the novel TAUHOU, but maybe it is a short, short story. It has its own power that is for certain:

BLANKETS

I am in the back of my father’s car. My sisters are here too and we are driving through a small beach settlement. The houses are prefab weatherboard, rundown, with junk in the front yards. It’s sunny, clear, and co…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sounds Good! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.