Appreciating John Bonham (Again)

I recently finished reading Beast: John Bonham and the Rise of Led Zeppelin. Look, it’s not great. Don’t rush to read it – but as is so often the case with a music bio, I loved the journey it helped to facilitate. My criticism of the book is that there’s not enough of interest in the early life of the drummer to warrant a full biography in this way; the analysis of his playing and contributions isn’t quite strong enough to redeem it either. So, we’re left, ultimately, with yet another retelling of the Zeppelin timeline. And there’s enough of that out there already.

There’s a wee clue in the blurb. It boasts about being the first full bio of the band’s drummer. Over 40 years after they split, maybe there wasn’t ever enough of a story to tell and that’s why no one had bothered, previously.

But, it had me going back through the catalogue and listening to the music again – and of course with special attention to the drums. Not so hard to do with Led Zep.

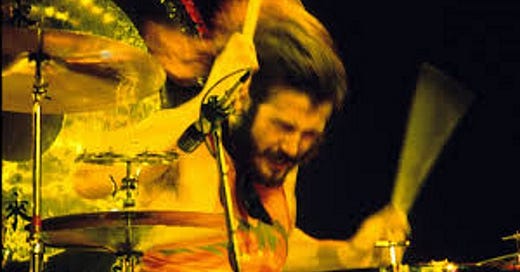

Bonham – or “Bonzo” as he was known – is one of my favourite drummers. And, in a band of virtuoso players, I feel that he was often the difference for Led Zeppelin, the component that made them stand out.

Listening to any of the band’s albums is the instant proof of his magic behind the kit – but the live recordings – both official and bootlegged – show him to be a percussion composer: live, he actually composes as he plays, choosing drums for fills for texture; choosing strokes via stick or hand to accent what he played in the moment/s before, to set up what he was about to think to play. Every move a backup of the move that had just been made – or was in anticipation of what was to come.

That should be how anyone/everyone plays the drums – but it is hardly ever the case.

I first heard John Bonham when I first heard Led Zeppelin. I was 14. And it – quite honestly – changed my life.

Always a stickler for a good drummer, for a huge drum sound, I couldn’t believe my ears when I heard my brother’s copy of Re-Masters. I was sure I was hearing multiple bass-drums for Good Times Bad Times – and the choice of fills during the subdued numbers like All My Love was instantly inspiring.

Bonham had power as a chief weapon, sure. But there was a lot of subtlety in the way he played – and he knew how to sit on a groove (listen here to the drum-only outtakes of Fool In The Rain where Bonham appropriates the Purdie Shuffle).

A writer of some note got into an argument with me once, about how Bonham was just a big iron-footed thug. I can’t handle this kind of non-thinking. This is the logic one might possess if all they’d ever heard was a greatest hits album – or more likely the handful of songs that classic rock radio favours. For, even to listen through to one of the many Zeppelin compilations is to hear subtly and magic in and around and informing that mighty power. There was a huge bass drum sound, and those awesome triplets doing the work many might only manage with two pedals, but Bonham also had a feather-touch behind the kit.

And yet, it is the power that people think of – and somewhat understandably.

It doesn’t have to just be the live drum solos – think of Achilles Last Stand, which is just one example of a Led Zeppelin song that is driven by Bonzo – carried by Bonham being just the right example of carried away, taking the song with him at every step – rather than just hitting cymbals and creating fills to impress. It’s an endurance feat to this day, a good test of a rock drummer that thinks they have chops and speed and skill; get them to play that, make no mistakes, then send them out to the world…

My favourite Zep album – if I had to pick one – is Physical Graffiti – but every single album is buoyed by Bonham’s drumming, fresh still because of his ideas. He had a feel that cannot be replicated – and the fact that he is still so often held up as a guru for hard-rock/metal drummers is, in so many ways, a testament to the ideas he got down on tape.

I also love listening to one of the most famous Zeppelin bootlegs, Destroyer. Bonham is on fire – giving the songs new meanings live. He seemed to live for the live moment, for the spontaneity, inching a new definition i to a song by elbowing in a different fill or stroking the skin of the drum sans sticks. He was always thinking as he played.

What a joy it was, when reading this book, to listen to the highlights, find new favourites and just revel in the very best of this band.

Bonham’s early life isn’t very remarkable because, really, it’s still his early life being served in Led Zeppelin. He was still a teenager when the band started. He had met Robert Plant in two earlier bands, they’d shared the stage as part of The Crawling King Snakes and then Band of Joy. Their bond was obvious throughout Zeppelin.

But Bonham couldn’t really cope with being on the road. So, he drank. He missed his wife. He was somewhat emotionally stunted. And he drank to compensate. To cope. To escape. The way so many problem drinkers do. That’s the great sadness there because we know that it is what ended Bonham’s life. A decade and a bit in Zeppelin, his genius all over all ten of the band’s studio albums. And then the candle is snuffed out. He is only just in his 30s. That cannot make the book a happy read. Whatever celebration there is, of the music, the legacy, comes to a halt when we consider the ending. An ending that most music fans are aware of, even if the full details aren’t on instant recall. But it’s a tragedy. And he couldn’t be saved. And seemingly didn’t want to help himself at all, well, you often can’t see you’re in a hole when you’re in the hole. In fact, you just can’t see at all.

Every so often I go on a bit of a Led Zep kick. I go through all the albums, the way I do with The Beatles. It’s a similar situation. Finite catalogue, the band’s reunion chances ultimately snuffed by the death of a key member – and that enormous and ongoing influence, their forever legacy. Some people say that Led Zeppelin is The Beatles of heavy metal. You say it like that, it sounds clunky. But there’s a truth in there somewhere. In terms of the monumental influence.

The last time I listened to a lot of Led Zeppelin albums in a row was a couple of years ago. My son, Oscar, was just starting to get into them. And he fell heavy. He rates them as one of his favourite musical acts. Right now, he’s on a hip-hop kick. But he said to me just the other day that he’ll always love The Beatles and Led Zeppelin – and it’s mostly because of the drums. That’s a smart call, since as a hip-hop fan he’s all over the drums and hearing that first. And both Ringo and Bonham were sampled heavily on the first two albums by another favourite band that Oscar and I share: The Beastie Boys.

Every member of Led Zeppelin was incredible. The band would not work without them. I’m burying the Led(e) here somewhat, but I was lucky enough to have a phone conversation with John Paul Jones. Even more amazing, I found out about the call roughly one hour before it happened. Oh yeah, and it was an interview too – I had to pull together some sort of question line, not just “you were in Led Zeppelin, eh? That musta been awesome!”

Seeing Robert Plant in Wellington in 2013 was incredible too. As I wrote here, a wee while back, Plant just continues to be a class act.

Now, Jimmy Page is problematic – and the magic powder long ago turned to dust and disappeared in the wind. But when he blazed on the stage, he had something that few others could ever get close to. And the vulnerability, the downright sloppiness in some of his playing was, in a weird way, perhaps his greatest strength.

But today, I’m thinking about Bonham. The beast. The engine that fired up Led Zeppelin. So, I made a 40-track playlist of what I consider Bonham’s Best. Look, it’s three and a half hours of Zep tunes, and most of the obvious ones but maybe it’s in a different order to how you normally listen. And it’ll include one or two songs you might not know, unless you know the entire catalogue. It’s also designed to hear with the drums in mind. These aren’t just Zep’s best songs, these are Bonham’s best performances; showcases for his special magic.

Compare them to when he was just starting out, a nervous teen doing his beat-combo thing with other nervous teens… A member of The Senators, playing a perfunctory cover of She’s A Mod, which Kiwi music fans from the 60s will know for Ray Columbus’ more charming cover.

Another thing, there’s this guy on YouTube with a channel called BONHAMOLOGY. He plays through all the Zep songs in the style of Bonham. It’s really quite incredible. He not only plays the studio versions, but also some of the key live performances.

I’m currently besotted with this entire show from 1971 in Osaka. Nearly three hours of a drummer in his practice room hitting it out of the park. I realise I’ve lost a lot of you with too much drum talk, but this made me profoundly happy to see and hear and feel.

Now, if that really was too much drum talk, you can at least enjoy Vol. 69 of the weekly playlist, A Little Something For The Weekend…Sounds Good! And a happy weekend to you all indeed. Thanks, as always, for reading.